Insults are some of the best words around (just check out this list), which arguably makes them great adoptees. (And while it might be tempting to adopt an insult in someone’s name, keep in mind you’ll need that someone’s permission.) Here are 10 of our favorite insults that you can still adopt for your very own.

troglodyte

In simplest terms, the term troglodyte is used to refer to someone thought to be “reclusive, reactionary, out of date, or brutish.” You can also use it to compare someone to an ape, a member of a prehistoric race of people who lived in caves, or a creature that lives underground, like a worm. The word comes from the Latin Trōglodytae, “a people said to be cave dwellers.”

sycophant

Know a spuriously submissive someone who likes to curry favor? You’ve got yourself a sycophant. This word comes from the Greek sūkophantēs, “informer,” which comes from sūkon phainein, which means “to show a fig.” So what does showing the fig mean? The Online Etymology Dictionary says it “was a vulgar gesture made by sticking the thumb between two fingers, a display which vaguely resembles a fig, itself symbolic of a vagina,” and it’s thought that “prominent politicians in ancient Greece” refrained “from such inflammatory gestures, but privately urged their followers to taunt their opponents.”

miasma

Then there’s the person who adept at creating a noxious atmosphere, literal or not. Miasma is the word for them. The word comes from the Greek miainein, “to pollute.”

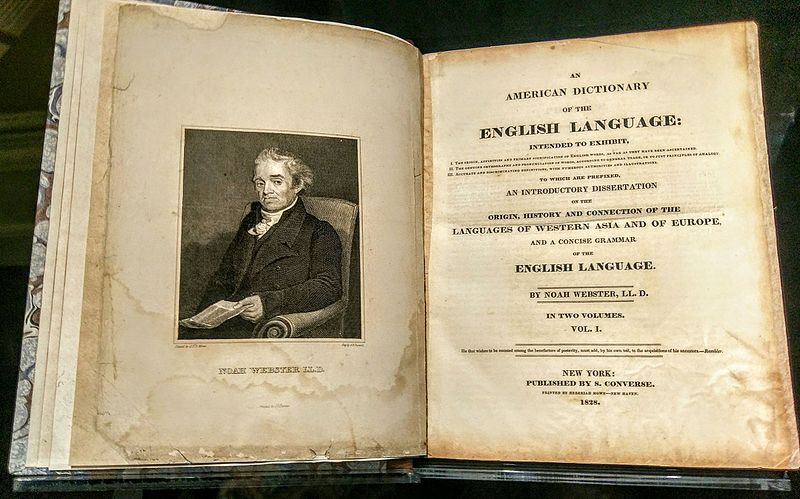

dilettante

A little dab’ll do ya, especially if you’re a dilettante. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) says the word first referred simply to a “lover of the fine arts,” especially “one who cultivates them for the love of them rather than professionally.” The term gained the meaning of an amateur artist but then came to be used derisively to mean someone “who interests himself in an art or science merely as a pastime and without serious aim or study.” As an adjective, it means superficial or amateurish.

sciolist

Know a know-it-all who doesn’t know it all? You’ve got yourself a sciolist, someone who has only superficial knowledge about a subject but claims to be ab expert. The term comes from the Latin sciolus, “one who knows a little,” and first appeared in English around 1612.

milquetoast

We suppose you can’t get much weaker than milk-soaked toast. This term for someone meek and timid is named for Caspar Milquetoast, a character created by American cartoonist H.T. Webster in 1924. The name comes from milk toast, an actual dish of buttered toast served in milk with sugar and other seasonings. A similar, much earlier term for someone considered feeble and ineffectual is milksop, which is from the late 14th century according to the Online Etymology Dictionary while milksop the dish (bread soaked in milk) came afterward, in the late 15th century.

poltroon

Need a good word for a coward? Poltroon at your service. The word comes from the Italian poltrone, “lazy fellow, coward,” which apparently comes from poltro meaning couch or bed. That might come from the Latin pullus, “young of an animal.”

quidnunc

The excellent quidnunc is perfect for the nosy gossip. It comes from the Latin quid nunc meaning “What now?” and, according to the OED, first appeared in English in a 1709 issue of a “society journal” called Tatler: “The insignificancy of my manners to the rest of the world makes the laughers call me a quidnunc.”

Philistine

This word for a smug or ignorant person “regarded as being indifferent or antagonistic to artistic and cultural values” or one who “lacks knowledge in a specific area” has somewhat complex origins. It originally referred to an ancient people “who made war on the Israelites,” says the Online Etymology Dictionary, and first appeared in English in the early 14th century. By 1600 it was used humorously to mean a “member of a group regarded as one’s enemies,” says the OED. Around 1824, it gained popularity at German universities as a derogatory term for townies or non-students, and by 1825 came to refer to an uneducated or unenlightened person.

mountebank

Charlatan is already a pretty great word, but how about mountebank? While now referring to any flamboyant huckster, the word originated in the 1570s to mean a doctor who stands on a bench to hawk “his infallible remedies and cures.” It comes from the Italian montambanco, a contraction of monta in banco, which means “quack” or “juggler” and translates literally as “mount on bench.”

Want even more word adoption ideas? Check out the 10 coolest words we still can’t believe are unadopted, and four wunderbar German loanwords that are also available.