Last week the 2015 nominees for the James Beard awards were announced. Among the nominated are mostly chefs and restaurants, but also included are food writers. Food plus words, what’s not to love?

In celebration, we’re taking a look at the language of taste.

gustatory

“She was if the word gustatory had grown legs and got a dress.”

William Giraldi, “The Style of a Wild Man,” The Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2011

Gustatory means related to the sense of taste. Gustatory receptor cells are chemoreceptors that detect taste, says How Stuff Works, while gustatory hairs are “spindly protrusions” on each receptor cell. The gustatory hairs interact with molecules and saliva to stimulate the sensation of taste.

The word gustatory comes from the Latin gustare, “to taste.”

kokumi

“Food scientists have been studying kokumi compounds in hopes of exploiting their enhancement qualities to create healthier, lower-salt or -sugar versions of foods that still taste good.”

Lisa Bramen, “The Kokumi Sensation,” Smithsonian.com, January 27, 2010

Kokumi translates from Japanese as “heartiness” or “mouthfulness,” says Smithsonian.com. It refers to “compounds in food that don’t have their own flavor, but enhance the flavors with which they’re combined.” Such compounds include calcium, protamine, and glutathione.

palate

“Even Howell admits that his palate is at its sharpest in the morning, when he claims to spend a full 45 minutes pondering his first cup of coffee.”

Corby Kummer, “The Magic Brewing Machine,” The Atlantic, December 1, 2007

Palate refers to both the roof of the mouth and the sense of taste. The Online Etymology Dictionary says the roof of the mouth was “popularly considered [to be] the seat of taste, hence [the] transferred meaning ‘sense of taste.’” Both meanings are from the late 14th century.

papilla

“We like to think of these bumps as our taste buds, but actually, these bumps are known as papillae.”

Amanda Greene, “Making ‘Sense’ of Flavor: How Taste, Smell and Touch Are Involved,” The Huffington Post, September 27, 2013

A papilla is a round or cone-shaped protuberance “on the top of the tongue that contain taste buds.”

The Huffington Post describes four different kinds of papillae. In the center of the tongue are filiform, “small, skinny papillae that almost look fur-like,” and which don’t contain taste buds.

On the front and sides are fungiform, “round dot-like papillae” that typically contain three to five taste buds each. Foliate and circumvallate are in the back, and contain the mother lode of taste buds: more than 100 each.

Papilla comes from the Latin word for “nipple.”

parageusia

“Despite its name (‘parageusia’ is a medical term meaning ‘a bad taste in the mouth’), Zellersfield believes the public will taste sophistication in this beer.”

Amber DeGrace, “Upcoming beer releases worth traveling to try,” Lancaster Online, February 20, 2015

Parageusia is “the abnormal presence of an unpleasant taste in the mouth, sometimes caused by medications.” The word is Greek in origin and comes from para, “against, contrary to,” and geusis, “taste.”

sapor

“While the Italian beans (Italian cut green beans) looked from-a-can, they tasted amazing, benefitting from bacon sapor.”

Matt Wake, “Little Diner’s gargantuan Happy Burger lives up to its rep and Huntsville restaurant’s pot roast is pretty legit too,” AL.com, July 8, 2014

Sapor is a taste or flavor, and comes from the Latin sapere, “to taste.” Sapere also means to be wise and gives us words like savvy, sapient, sage, and savoir faire.

supertaster

“People with lots of papillae usually experience tastes more intensely — they’ve been dubbed ‘supertasters.’”

Allison Aubrey, “Why ‘Supertasters’ Can’t Get Enough Salt,” NPR, June 21, 2010

It could be said that supertasters have hypergeusia, an abnormally heightened sense of taste (to be ageusic means to have no sense of taste).

One might also assume that supertasters need less salt. After all, according to NPR, supertasters “need less fat and sugar to get to the same amount of pleasure than a non-taster does.” But a study actually found that supertasters prefer “high-sodium items” such as chips and cheeses.

Why this is the scientists aren’t sure. One speculation is that “as people perceive smaller differences in things, it becomes more desirable to seek those things out.” Another hypothesis is that supertasters find “bitter flavor notes” unpleasant and salt “knocks down bitterness.”

The term supertaster was coined in the early 1990s, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

tongue map

“Although there are subtle regional differences in sensitivity to different compounds over the lingual surface, the oft-quoted concept of a ‘tongue map’ defining distinct zones for sweet, bitter, salty and sour has largely been discredited.”

Claiborne Ray, “A Map of Taste,” The New York Times, March 19, 2012

The tongue map was developed by German scientist D.P. Hanig in 1901, says How Stuff Works. It was first discredited in 1974, and again most recently in a 2010 paper in The Journal of Cell Biology.

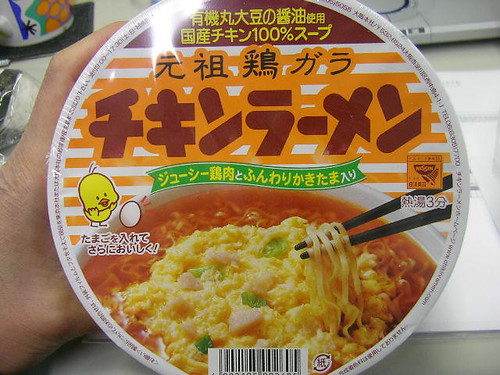

umami

“Chefs including Jean-Georges Vongerichten are offering what they call ‘umami bombs,’ dishes that pile on ingredients naturally rich in umami for an explosive taste.”

Katy McLaughlin, “A New Taste Sensation,” The Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2007

Umami, sometimes called the fifth taste after sweet, salty, bitter, and sour, is Japanese in origin. It’s a rich, savory flavor, often associated “with meats and other high-protein foods.”

In the early 1900s, Japanese scientist Kikunae Ikeda identified the flavor and coined the word. Because Ikeda wrote in Japanese, umami’s first appearance in English wasn’t until the early 1960s, says the OED.

Now scientists say there might be a sixth taste: fat. Other tastes up for consideration are alkaline, the opposite of sour; metallic; and water-like.

For even more delicious words, check out some of our favorite food terms.

[Photo via Flickr:”Umami Burger in LA, CA,” CC BY 2.0 by G M]