We’ve brought you words about reading and words about writing. Now it’s time for the last of the three Rs: arithmetic.

Arithmetic, “the theory of numbers; the study of the divisibility of whole numbers, the remainders after division, etc.,” comes from arithmos, the Greek word for “number” (arithmein means “to count”). Arithmos brings us number-related words such as arithmometer, “an instrument for performing multiplication and division”; arithmocracy, “rule or government by a majority”; arithmancy, “divination using numbers that are the equivalent of letters of a name”; and arithmomania, “a morbid impulse to work over mathematical problems, or to count objects or acts, such as buttons, steps, etc.” (which apparently afflicts vampires in particular).

Arithmos also gives us logarithm, “for a number x, the power to which a given base number must be raised in order to obtain x,” “coined by Scottish mathematician John Napier” in the 1610s, with the Greek logos meaning “proportion, ratio, word.” (John Napier was also the inventor of Napier’s bones, “a set of numbered rods used for multiplication and division.”)

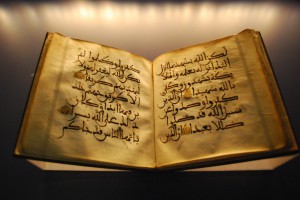

A word often mistakenly attributed to arithmos is algorithm, “a precise step-by-step plan for a computational procedure that begins with an input value and yields an output value in a finite number of steps.” Algorithm is actually an alteration of algorism, “the Arabic system of notation; hence, the art of computation with the Arabic figures, now commonly called arithmetic,” which comes from the Middle Latin algorismus, “a mangled transliteration of Arabic al-Khwarizmi ‘native of Khwarazm,’ surname of the mathematician whose works introduced sophisticated mathematics to the West.”

Algebra comes from the Middle Latin algebra, which comes from the Arabic “al jebr ‘reunion of broken parts,’ as in computation,” and was used in the 9th century by Baghdad mathematician, Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, as the title of his famous treatise on equations (‘Kitab al-Jabr w’al-Muqabala’ ‘Rules of Reintegration and Reduction’), which also introduced Arabic numerals to the West. In 15- and 16-century English, algebra was used “to mean ‘bone-setting,’ probably from Arab medical men in Spain.”

Geometry, “that branch of mathematics which deduces the properties of figures in space from their defining conditions, by means of assumed properties of space,” comes from the Greek geōmetrein, “to measure land.” Related to geometry, aside from all those geo- words, is gematria, “a cabalistic system of Hebrew Biblical interpretation, consisting in the substitution for a word of any other the numerical values of whose letters gave the same sum.” Trigonometry, “the branch of mathematics that deals with the relationships between the sides and the angles of triangles and the calculations based on them, particularly the trigonometric functions,” contains the Greek trigōnon, “triangle.”

Calculus, “any highly systematic method of treating a large variety of problems by the use of some peculiar system of algebraic notation,” comes from the Latin calculus, “reckoning, account,” which meant originally “small stone used in reckoning,” and is diminutive of calx, “small stone for gaming” or “limestone.” In pathology, calculus refers to “inorganic concretions of various kinds formed in various parts of the body” while the root calx brings us a number of counting and stone-related words. There’s calcium, calcified, and calcific. There’s chalk and caulk. There’s calculating and calculator.

Speaking of calculators, check out these ancient calculating devices, including the quipu, “a recording device, used by the Incas, consisting of intricate knotted cords”; the abacus, which comes from the Greek abax, “counting board,” which may have come from the Hebrew ‘ābāq, “dust”; and the jetton, “a piece of metal, generally silver, copper, or brass, bearing various devices and inscriptions, formerly used as a counter in card-playing, or in casting up accounts.” Jetton comes from the French jeton, “coin-sized metal disk, slug, counter,” which may have also brought us jitney, a small bus, “perhaps because the buses’ fare was a nickel,” like a jeton.

Want more? Check out this mathematical list, these mathematical delights, and these mathaphors. Or you may like these really really large numbers, these imaginary numbers, or these different ways to say zero.

There’s a positive googolplex of words about math and numbers. These are just a few.