Adidas or Reeboks. Pumas or Jordans. Keds or Vans. Whatever kind you wear, they all have one thing in common. They’re called sneakers.

Or are they? Just as there are innumerable sneaker brands and styles, there are a plethora of names for that casual, rubber-soled shoe. Here we take a look at some of them from across the United States and around the globe.

“Sneaker” or “tennis shoe”?

Sneaker and tennis shoe are neck and neck for most popular term in the U.S. According to the Harvard Dialect Survey, 45.5% of Americans say sneaker while 41.34% say tennis shoe.

The use of sneaker, says the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE), is widespread but somewhat more frequent in the Northeast and North Central states. Meanwhile, tennis shoe is less frequent in the Northeast.

While sneaker is slightly more popular than tennis shoe, the latter is about eight years older. The earliest citation in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is from Rudyard Kipling’s 1887 short story, “The Bisara of Pooree“: “It was his wizenedness and worthlessness that made him fall so hopelessly in love with Miss Hollis, who was good and sweet, and five-foot-seven in her tennis-shoes.”

Some sneaky (and tennie) variations

While sneaker and tennis shoe dominate U.S. vernacular, you might hear some variations thereof.

In the Northeast, someone might say sneaks for sneakers. In western Pennsylvania and the Great Lakes region, tennis shoes might be called tenners. Scattered throughout the country but chiefly in the western Great Lakes, Iowa, and the West (but not the Northwest), you might get tennie, while in the Northwest the preferred term seems to be tennie-runner. In the Southern region, you might hear tennie-pump, tennies, or simply tennis.

More U.S. sneaker slang

Regional variations don’t stop at these alterations. Back in the day, you might have heard ball shoe in the South Midland states. Going for a run in southern Louisiana? You’ll need your decks, short for the sneaker-esque deck shoe. In Montana, Ohio, and Mississippi, your tennies might be known as quick starts while in the Gulf States and South Carolina, you might take a walk in your easy walkers.

Highs and lows

Sneakers are referred to by their style. Low-top meaning any low-topped shoe or boot originated in 1892, says the OED, and came to refer specifically to sneakers in the late 1980s. As for high-top, the OED’s first mention is from 1895, again meaning a regular shoe or boot, while the sneaker meaning is from 1985.

So that’s how sneaker slang runs in the U.S. How about across the pond?

Running shoes, training shoes, and runners

The oldest term for a rubber-soled athletic shoe in British English seems to be running shoe, which originated around 1666, says the OED. (According to the Harvard Dialect Survey, about 1.42% of Americans refer to their Nikes as such.) Almost 200 years later, training shoe came about, and another 130 years later, the shortened trainer, which is also used in Glasgow, Scotland, says lexicographer Susie Dent in her book How to Talk Like a Local: From Cockney to Geordie, a national companion. The Australian English runner is from 1970.

Plimsolls

First appearing in print in 1885, according to the OED, the now genericized brand name was suggested in 1876 by “an energetic sales representative” of the Liverpool Rubber Company “for the new canvas rubber shoes or sand shoes then becoming fashionable for wear on seaside beaches.” The shoes’ rubber band reminded the sales rep of the Plimsoll Line, which marks “the limit of safety to which merchant ships can be loaded.” Similarly, the shoes’ own “water-band” marked how far they could be immersed in water and still remain “water-tight.”

Variations include plimmies and plimsoles, influenced by sole, the underside of a shoe or foot, and used by James Joyce in Finnegans Wake: “Their blankets and materny mufflers and plimsoles.”

For even more on plimsolls and sneaker speak, check out this great post from Fritinancy.

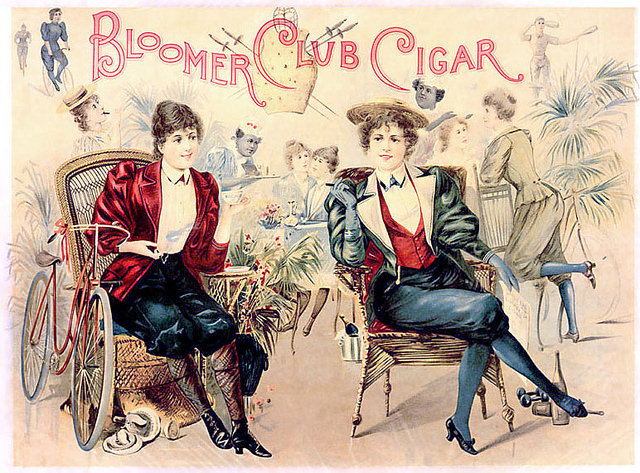

Pump(s) up the jam

Like Dent says, the word pump has been used to describe a variety of shoes since 1555, including a “close-fitting, low-heeled shoe,” slippers, and a shoe for acrobats and dancers. It seems to be around 1897, says the OED, that pumps also referred to sneakers. From the Sears, Roebuck catalog: “Men’s gymnasium shoes… Men’s low cut canvas pumps, canvas sole, [etc.].” Now pump is a regional term, which, says Dent, “dominates the North and Midlands.”

Track shoes and daps

About a decade after pump came track-shoe, followed in 1924 by dap, which might come from the verb sense of the same word meaning to dip lightly, or to skip or bounce.

Sannies, gutties, and tackies (oh my)

According to Dent, sandshoes or sannies have been around since the mid-19th century, and are standard terms in Scotland as well as “the North-East as far south as Hull.”

Gutties is another sneaker saying from Scotland. According to the Herald Scotland, guttie comes from gutta-percha, “a rubbery substance derived from the latex” of certain tropical trees, and “used as an electrical insulator, as a waterproofing compound, and in golf balls” (A gutta or gutty is a golf ball made of such material.) Gutta-percha is Malay in origin, where getah means “sap” and perca, “strip of cloth.”

Tackies is said in South Africa, but the word is “apparently not Afrikaans,” says the OED. It might come from tacky meaning slight sticky or gummy to the touch.

What are you wearing? Mutton dummy.

The curious and wonderful mutton dummy is a Northern Irish term. According to the Oxford Living Dictionaries, it might have originated in the 1930s, “possibly from mutton cloth, ‘a type of cotton cloth used to wrap meat’ (from the resemblance to the material from which the shoes are made),” and dummy, “with reference to the lack of noise they make.”

Puss boot is from Jamaican English, and probably represents “a humorous folk reference to the soft tread of a person in such shoes,” says the OED.

What do you call sneakers?