Image credit: OUP

Why is the English language so complicated, so illogical, and so weird?

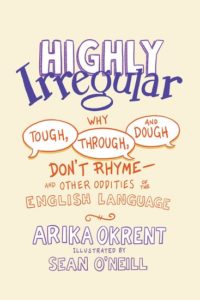

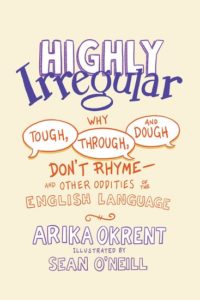

Everyone has thought it, from the most seasoned writers to the newest English language learners. In her new book, Highly Irregular: Why Tough, Through, and Dough Don’t Rhyme—and Other Oddities of the English Language [Bookshop.org, Amazon, OUP], author and linguist Arika Okrent sets out to explain some of the language’s most notorious contradictions—and, along the way, paints a delightfully engaging picture of the language’s history, from its Germanic origins to the latter-day pedants who insist on keeping English irrational.

Dr. Okrent spoke with us about working on the book, and about English past, present, and future.

Your book addresses the questions people like to ask about the English language: things like “why do we park on a driveway and drive on a parkway?” Of all these questions, were there certain ones that you heard again and again, even before you started writing Highly Irregular? Do you think that people are actually interested in learning the answers, or do we just like complaining and asking rhetorical questions about English?

The only ones that I heard more than once were the joke ones, like driveway/parkway, no egg in eggplant, or “why do noses run and feet smell,” and no, people don’t bring those up really wanting to know the answer. The winking complaining is the point. But the thing they’re complaining about, that English can be so illogical and unsystematic, is important, as any person trying to learn it as a second language (or child learning it as a first language) can tell you. It’s also very interesting! There is a “why” and it tells you something about how languages develop. The really good questions came from kids or non-native speakers. Why don’t we spell “of” with a v? Why do we order a “large” drink and not a “big” one? It takes a bit of an outsider perspective to even see these.

image credit: Sean O’Neill

One thing that makes Highly Irregular so much fun to read is the accompanying cartoons by artist Sean O’Neill. How did that collaborative process work, and how did you decide which examples were going to be illustrated?

We started working together on a series of whiteboard videos for Mental Floss, little two or three minute explanations of various language topics. I would write a script, he would come up with some drawings to go with it, film himself drawing them on a whiteboard, and then I would edit it

together and record the script as a voiceover. In the very beginning, I would write the script with some idea of what he could use to make things visual, trying to pick examples that were drawable, but he would always come up with something great that I hadn’t thought of at all. So I stopped thinking of things visually when writing (I’m totally a word person, not a picture person!) and just trusted him to find the way into the drawing.

I did the same for the book. I just gave him the sections as I finished them and he would come up with three or four drawings for each one. I love how he really brings people to life. I think we language folks have a tendency to think about the history of language very abstractly–the movement of sounds, lexemes, meanings, grammatical templates–but it’s all people, real people using those things, in 400 AD, in 1476, in 1890, and today. It’s nice to see them in action, even in [a] cartoon version, a reminder that it’s not words themselves that change meaning, but people using those words.

Highly Irregular addresses a lot of the specific particularities of the English language, but it also does a great job of dispelling myths about English, and about language in general: how languages develop, how they get standardized, and so on. Are there particular takeaways you really wanted to impart on your readers, or broader philosophical ideals that inform the work?

I think people generally know, and accept, that language changes, but a lot of the illogical bits in language come from the fact that language also stays the same. Certain parts resist the change around them and they become fossils, part of the language today, but stuck with the forms of a previous era. Language is two opposing things at once: an infinitely creative tool for expressing any kind of meaning that comes along in the world, and a very conservative tradition that must be stable enough to pass from one generation to the next. We are able to say things that have never been said before, while most of the time repeating the same things over and over again. The repetition embeds and entrenches habits. The creativity introduces departures from the habits. It needs to be both. It’s amazing that it’s both!

What about your takeaways—has writing Highly Irregular changed the way you speak, write, read, and listen to the English language? Do you notice things you wouldn’t have before?

Of course I’ve become much more attuned to the questions, the moments of “wait, what’s up with that, English?” I love hearing “mistakes” from kids or non-native speakers because they usually brilliantly capture what the rule should be but for some reason isn’t. And then I want to know the reason.

Finally, how is English going to continue becoming even more irregular? Might we soon have to add new categories of blame: “Blame the Internet,” for example?

It’s really hard to predict what might be irregular in the future. Like, could a speaker of Old English even imagine that we would totally change the way we do past tense verbs? Would a typesetter in the early days of the printing press ever think that we might come to fret so much about spelling when it really wasn’t considered very important at the time? I do think the internet and social media are having a major effect on language in the way that connectivity speeds up the pace of spread of language innovations and in the way it has made possible a written version of real time, spontaneous, casual communication. What sort of mistakes might kids of the future, just learning to communicate online, make in this area? The question doesn’t even make sense, because when it comes to online communication we accept that whatever the kids are doing is what it is. It’s the older generations who don’t get the rules quite right.

[Note: Bookshop.org and Amazon links are affiliate links. By purchasing through these links, you help support Wordnik’s nonprofit mission to find and share all the words of English.]

![]() Here’s how it works:

Here’s how it works: