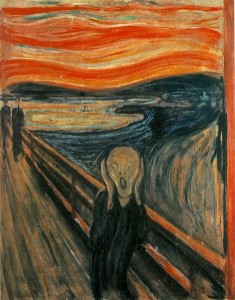

Boo! Did we scare you? No? Maybe these 10 ghostly words will give you the screaming abdabs instead.

boo

“Harlin relies on cheap ‘Boo!’ scares more often than any film needs, which was never the point of this franchise, but merely what other filmmakers (or producers) have reduced it to.”

Brian Orndorf, “Review: Exorcist: The Beginning,” Film Fodder, August 21, 2004

In addition to “a loud exclamation intended to scare someone,” boo also means “a sound uttered to show contempt, scorn, or disapproval.” Douglas Harper, the founder of the Online Etymology Dictionary, says:

Common people had few opportunities to gather in a mass and express disapproval through much of Western history, but when they did, loud, insulting barnyard noises tended to be their weapon of choice. . . .These included hissing, like a goose, or booing, like a cow.

Boo is also slang for “a close acquaintance or significant other,” perhaps as an alteration of beau.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, boo as a scary exclamation seems to have originated in the early 18th century as a “word used in the North of Scotland to frighten crying Children.” To say boo to a goose means “to speak up, to stand up for oneself.” For how to say boo in other languages, check out this post from the Virtual Linguist.

dobby

“On the stairs certain bloodstains are pointed out, said to be those of a lady who was killed in the glen below, and who was afterwards known as the ‘Mortham dobby.'”

John Murray, Richard John King, Handbook for Yorkshire

A dobby, in addition to being a well-known house-elf, is “a sprite or apparition.” Also spelled dobbie, the word seems to derive from the common name Robert, and in Sussex is known as Master Dobbs.

fetch

“The ‘fetch‘ is supposed to appear when the person whose ‘counterfeit presentment’ it is happens to be at the point of death.”

“‘Fetch,’ Its Derivation and Use,” The New York Times, December 24, 1899

A fetch is “ a ghost, an apparition; a doppelgänger.” While the origin of fetch is largely unknown, it seems to come from Ireland, according to the OED.

Fetch may be short for the earlier fetch-life, “a messenger sent to ‘fetch’ the soul of a dying person,” where fetch means “to go and bring.” This sense of fetch comes from the Old English feccan, “apparently a variant of fetian, fatian ‘to fetch, bring near, obtain; induce; to marry.’”

larva

“’It is a dead thing!’ said Glaucus.

‘Nay – it stirs – it is a ghost or larva,’ faltered lone, as she clung to the Athenian’s breast.”

Edward Bulwer Lytton, The Last Days of Pompeii

While most of us know larva as “the newly hatched, wingless, often wormlike form of many insects before metamorphosis,” it’s also, in Roman mythology, “a malevolent spirit of the dead.”

The word comes from the Latin lārva, “specter, mask,” with the idea that the wormlike form “acts as a specter of or a mask for the adult form.”

pareidolia

“This psychological phenomenon is called pareidolia. It is when random images or sound are perceived as something non-random. This is always a danger in paranormal research, for instance when people believe they see a face in the static of a video.”

Alejandro Rojas, “Recording Ghost Voices: The Electronic Voice Phenomenon (EVP) ,” The Huffington Post, October 23, 2011

Pareidolia is “a psychological phenomenon involving a vague and random stimulus (often an image or sound) being perceived as significant.” The word comes from the Greek para, “alongside, beyond,” and eidolon, “mental image, apparition, phantom.”

poltergeist

“‘In half an hour we were all sitting about the table in a dim light, while the sweet-voiced mother was talking with ‘Charley,’ her ‘poltergeist‘–’

‘What is that, please?’ asked Mrs. Quigg.

‘The word means a rollicking spirit who throws things about.’”

Hamlin Garland, The Shadow World

A poltergeist is “a ghost or spirit that indicates its presence by the sound of moving objects, knocks, and similar noises.” The word is German in origin, coming from poltern, “to make noises,” plus Geist, “ghost.”

Apport is “the supposed paranormal transference of an object from one place to another, or the appearance of an object from an unknown source, often associated with poltergeist activity and séances.”

revenant

“While looking on this side and that side, striving to pierce their mysteries, taking a step this way and a step that, and trembling all the while lest she should see the revenant, said to haunt the place, a dreadful sound like the huge fluttering of large wings arose above in the arches.”

Mrs. Henry Wood, Charles William Wood, The Argosy

A revenant is “one who returns; especially, one who returns after a long period of absence or after death; a ghost; a specter.” The word comes from the French revenir, “to return.”

spook

‘”It made a lot of people come to see me,’ the youngster told county police yesterday between sobs as she admitted the spook that haunted the Henry Thacker family was her own creation.”

“Girl Admits Spook Hoax,” Reading Eagle, January 4, 1952

Spook may come from the Dutch spooc, “ghost.” According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, “the derogatory racial sense of ‘black person’ is attested from 1940s, perhaps from notion of dark skin being difficult to see at night.” Spook as slang for “secret agent, spy” is from 1942, perhaps from the idea of being hidden. Spooky, frightening, is from 1854, while the “easily frightened” sense is from 1926.

taisch

“As the Taisch murmurs the prophecy of death in the voice of one about to die, so does the Wraith, Swarth, or Death-fetch, appear in the likeness of the person so early doomed to some living friend of the party; or as in some rare instances, even to the individuals themselves.”

Walter Cooper Dendy, On the Phenomena of Dreams, and Other Transient Illusions

A taisch refers to “the voice of one who is about to die heard by a person at a distance,” as well the “second sight.” According to the OED, the word comes from the Middle Irish tadhbais, “phantasm.”

wraith

“Banquo’s wraith, which is invisible to all but Macbeth, is the haunting of an evil conscience.”

Henry A. Beers, Chaucer to Tennyson

A wraith is “an apparition in the exact likeness of a person, supposed to be seen before or soon after the person’s death; in general, a visible spirit; a specter; a ghost.” The word is Scottish in origin, and may come from either the Old Norse vorðr, “guardian,” or the Gaelic arrach, “specter, apparition.”

Want more? Check out our posts on fear words, devil names, devil words and facts, vampire vords and accents, and words and phrases related to zombies and werewolves.