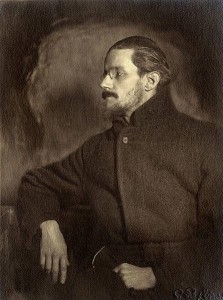

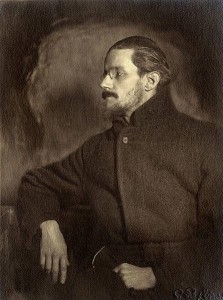

This Saturday, June 16 is Bloomsday, an annual celebration of Irish writer James Joyce and his novel, Ulysses.

Want to join the festivities? Follow in Leopold Bloom’s footsteps and take a walking tour of Dublin. Learn about the Irish capital through an app that “maps the locations of James Joyce’s modernist novel.” Attend a readathon with “more than one hundred Irish writers [reading] consecutively over 28 hours,” or listen to BBC Radio 4’s “five-and-a-half-hour adaptation of the novel.” Read Ulysses in its entirety (finally) at the Irish National Library. Or just enjoy this roundup of ten of our favorite Ulyssesean and Joycean words.

honorificabilitudinitatibus

“Like John o’Gaunt his name is dear to him, as dear as the coat and crest he toadied for, on a bend sable a spear or steeled argent, honorificabilitudinitatibus, dearer than his glory of greatest shakescene in the country.”

James Joyce, Ulysses

Honorificabilitudinitatibus means “the state of being able to achieve honors.” According to World Wide Words, Joyce borrowed it from Shakespeare, “who in turn borrowed it from Latin”:

I marvel thy master hath not eaten thee for a word;

for thou art not so long by the head as

honorificabilitudinitatibus: thou art easier

swallowed than a flap-dragon.

Love’s Labor Lost

But Shakespeare didn’t coin the word. Its first appearance, “in the form honōrificābilitūdo” was “in a charter of 1187 and as honōrificābilitūdinitās in a work by the Italian Albertinus Mussatus about 1300.” The word was also used “by Dante and Rabelais and turns up in an anonymous Scots work of 1548, The Complaynt of Scotland.”

inwit

“Speaking to me. They wash and tub and scrub. Agenbite of inwit. Conscience. Yet here’s a spot.”

James Joyce, Ulysses

Inwit, meaning “inward knowledge; understanding; conscience,” was coined in the 13th century, says the Online Etymology Dictionary, and comes from in plus wit. World Wide Words goes on to say that the word “had gone out of the language around the middle of the fifteenth century” and “would have remained a historical curiosity had not Joyce and a few other writers of his time found something in it that was worth the risk of puzzling his readers.”

The phrase agenbite of inwit echoes Ayenbite of Inwyt, a Middle English “confessional prose work.” Ayenbite or agenbite is “literally ‘again-bite’, a literal translation of the Latin word meaning ‘remorse’,” says World Wide Words.

monomyth

“At the carryfour with awlus plawshus, their happy-ass cloudious! And then and too the trivials! And their bivouac! And his monomyth! Ah ho! Say no more about it! I’m sorry! I saw. I’m sorry! I’m sorry to say I saw!”

James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Monomyth, a word that Joyce coined, is “a cyclical journey or quest undertaken by a mythical hero,” and today is most famously applied to Joseph Campbell’s concept in his writings about heroes, stories, and myth.

Mr. Right

“Be sure now and write to me. And I’ll write to you. Now won’t you? Molly and Josie Powell. Till Mr Right comes along, then meet once in a blue moon.”

James Joyce, Ulysses

Mr. Right refers to “a perfect, ideal or suitable mate or husband,” and, says the Online Etymology Dictionary, first appeared in Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922. However, we found Mr. Right in this context (not as someone’s name) in what appears to be a song from around 1826:

Mr. Right! Mr. Right!

Oh, sweet Mr. Right!

The girls find they’re wrong when they find Mr. Right

There’s some love the young, and the young love the old,

There’s some love for love, and some love for gold.

Many Pretty young girls get hold of a fright,

And all their excuse is – I’ve found Mr. Right.

If anyone has any additional information on the origin of Mr. Right, let us know!

poppysmic

“Florry whispers to her. Whispering lovewords murmur, liplapping loudly, poppysmic plopslop.”

James Joyce, Ulysses

Poppysmic refers to the sound “produced by smacking the lips.” The word comes from the Latin poppysma, says World Wide Words. The Romans used the word to refer to “a kind of lip-smacking, clucking noise that signified satisfaction and approval, especially during lovemaking,” and that “in French, it referred to the tongue-clicking tsk-tsk sound that riders use to encourage their mounts.”

pud

“For your own good, you understand, for the man who lifts his pud to a woman is saving the way for kindness.”

James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

A pud is a “a paw; fist; hand,” but is also apparently meant as slang for penis, says the Online Etymology Dictionary. Pud is short for pudding, which originally referred to “minced meat, or blood, properly seasoned, stuffed into an intestine, and cooked by boiling,” also known as sausage. Pudding gained the slang sense of penis in 1719.

quark

“— Three quarks for Muster Mark!

Sure he hasn’t got much of a bark

And sure any he has it’s all beside the mark.”

James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Quark is a nonsense word that Joyce coined in his novel, Finnegans Wake. Physicist Murray Gell-Mann, says the Online Etymology Dictionary, applied quark to “any of a group of six elementary particles having electric charges of a magnitude one-third or two-thirds that of the electron, regarded as constituents of all hadrons.”

schlep

“Across the sands of all the world, followed by the sun’s flaming sword, to the west, trekking to evening lands. She trudges, schlepps, trains, drags, trascines her load.”

James Joyce, Ulysses

While Joyce didn’t coin the word schlep, which comes from Yiddish shlepn, “to drag, pull,” its first known appearance in English seems to have been in Ulysses.

Ulysses

“In ‘Ulysses,’ Joyce follows Leopold Bloom, an advertising salesman, around Dublin through the course of one day in 1904 – June 16, a date that is now annually celebrated by Joyce scholars and admirers as ‘Bloomsday.’”

Herbert Mitgang, “Joyce Typescript Moves to Texas,” The New York Times, June 16, 1990

Ulysses is the Latin name for Odysseus, in Greek mythology, “the king of Ithaca, a leader of the Greeks in the Trojan War, who reached home after ten years of wandering.” The Odyssey and Odysseus gave us odyssey, “an extended adventurous voyage or trip”, or “an intellectual or spiritual quest.”

Ulysses contract

“The new paper takes precommitment strategies much further, advocating, for example, a ‘Ulysses contract’ — or a ‘commitment memorandum’ that spells out what to do when the markets move 25 percent up or down.”

Jeff Sommer, “The Benefits of Telling the Ugly Truth,” The New York Times, April 30, 2011

A Ulysses contract, says The Wall Street Journal, is a promise

not to act hastily in volatile markets. Just as Ulysses had his crew tie him down so he could resist the Sirens’ deadly song, Prof. Benartzi…would have investors promise not to overreact to sharp market moves in either direction.

Erin McKean says that Ulysses’s wife, Penelope, “also lends her name to a number of objects, including Penelope canvas (used for needlework), and to the verb penelopize, ‘to pull work apart to do it over again, in order to gain time.’”

Still jonesing for more Ulysses words? Check out this list and this one, and for more nonsense words like quark, check out this one.