Welcome to the latest installment of “Five words from …” our series which highlights interesting words from interesting books!

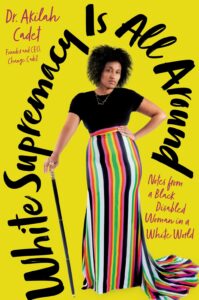

In White Supremacy is All Around: Notes from a Black Disabled Woman in a White World, Dr. Akilah Cadet shares her life and teachings to show the shadow structures in the United States (and beyond) that continue to give white, non-disabled, cis people advantages at the cost of others. Embracing the adage “when you’re used to privilege, equality feels like oppression,” she provides an actionable framework to label and dismantle white supremacy.

accomplice

“An accomplice is someone who uses their privilege to dismantle racism, oppression, and white supremacy … An accomplice uses their privilege as a road map to know how to show up for others. They are unafraid of what their fellow white peers will say as they embrace being the odd one out.”

Dr. Cadet illustrates the difference between an accomplice and an ally. For her, being an ally is a fair-weather state of being. An accomplice is the person creating daily habits and actions to call out oppression, with or without self-promotion.

intersectionality

“A term coined by Kimberle Crenshaw, intersectionality means the inner sections of our identities, who and what we are.”

“Where ethnicity, class, gender, and characteristics intersect.”

Depending on the situation, a white woman can choose to be seen as white or a woman. Being a Black, disabled woman, Dr. Cadet’s experiences are shaped by being unable to separate these identities; she is not given the opportunity to self-label when living in white dominant culture.

For more on intersectionality, see Kimberlé Crenshaw: The urgency of intersectionality and Intersectionality, explained: meet Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term.

intent

“The intent was not to harm but the outcome was just that.”

“‘That wasn’t my intent’ is an excuse to not do what you said you would do or evade accountability for harm or impact.”

When someone says something that offends another person, Dr. Cadet explains that the speaker’s intent may not have been to harm—but if it did, the speaker still needs to acknowledge accountability for unknowingly causing harm. When speakers refuse to recognize the impact of their words, it may be a way for them to hide behind bias and miss an opportunity to be an accomplice.

white centering

“When white people change the narrative of the story, situation, and harm caused to them–not the BIPOC person.”

Dr. Cadet meets a white woman who openly says the N-word during a presentation on the wine industry. Though Dr. Cadet asks her not to use it, the white woman still does. When confronted about it later, the white lady called the situation a “deeply emotional experience for me,” negating the experience and emotions of Dr. Cadet and instead placing herself and her feelings as the center of the story.

white supremacy

“White supremacy is a structure, system, process, policy approach, benefit and VIP club only for white people. It is the overt and covert racism that Black people experience, the feeling white people have of being superior and feeling like the best. Simultaneously, it is the feeling of resistance when being held accountable.”

Dr. Cadet acknowledges that people born into white privilege can have difficulty seeing and stepping away from it. No one loves the feeling of realizing they may have been wrong about something, or had advantages they weren’t fully aware of; Dr. Cadet stresses that the ability to learn and unlearn personal and systemic bias is key for those with various forms of privilege.

Got a book you’d like to see given the “five words from” treatment? Nominate it through this form, or email us!