Hwæt the heck?

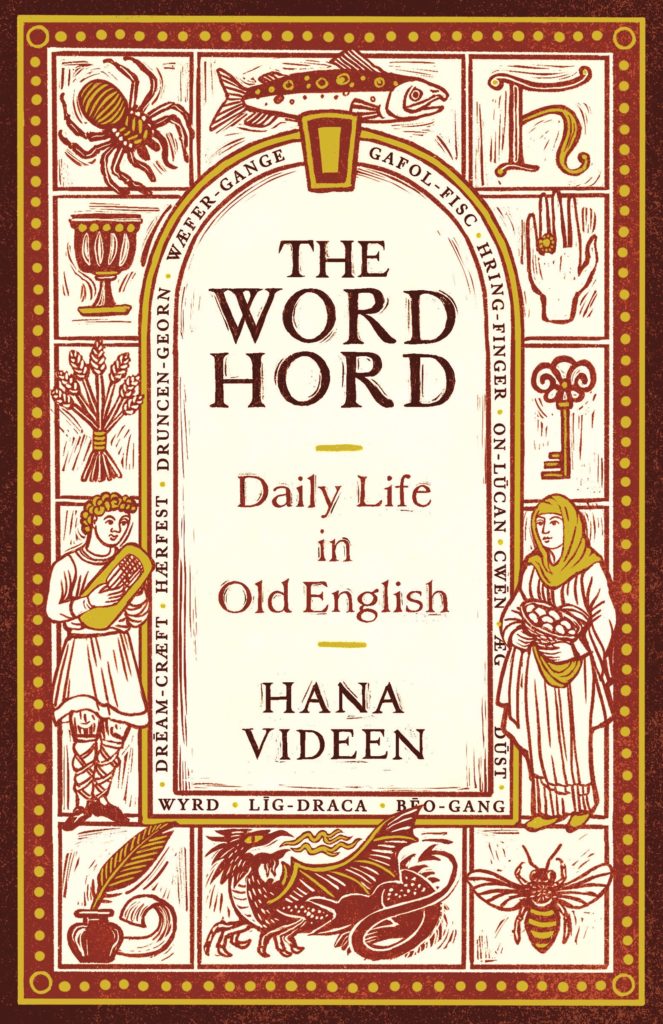

Old English is fundamental to the language we speak every day, yet few people outside medievalists and literature scholars know very much about it. Hana Videen is here to change that: in 2013, she started the Wordhord twitter account, posting one Old English word a day. She’s since expanded her efforts: the Old English Wordhord now encompasses a blog, an instagram account, and now a book.

The Wordhord, out this week, is an accessible and engaging lexicon of the language that would become English. Dr. Videen spoke with us about her favorite OE words, Medieval twitter, and how she put together the hord.

Are there any particularly frustrating myths and misconceptions that contemporary English speakers have about Old English? If there were one misconception you could correct, what would it be?

Old English is not Shakespeare … or Chaucer! It’s much older: the language spoken in what’s now England between the mid sixth to the mid twelfth centuries. It looks so much different from the English we know today. For instance, the first lines of Beowulf are:

Hwæt! We gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon…

It’s essentially a foreign language even to fluent modern English speakers. Despite this, it can sometimes look very familiar – Hana is min nama, for instance, looks very much like “Hana is my name.”

Also, the language is Old English, not “Anglo-Saxon”, as it has sometimes been called in the past. And the people who spoke it were englisc, or people of early medieval England. The term “Anglo-Saxon” was rarely used by the people of early medieval England to refer to themselves. “Anglo-Saxon” became popular in the nineteenth century alongside an imperialist, racist concept of a “noble Anglo-Saxon race” destined to conquer the world. Today it’s defended as a neutral and historical term – but it’s not.

Can you talk a little bit about your process selecting Old English “gems” for your Wordhord? Are there any words or categories of words that you wish you could have included?

For the words in The Wordhord I began by going through the “favorites” category on my blog. (These are my favorites – I changed the category to “hord highlights” after the Old English Wordhord app was launched, since people can favorite their own selection of words and that got confusing.) Then I thought about how I might group them in chapters within a book. I eventually decided to have each chapter focus on a different aspect of daily life: eating and drinking, religion, traveling, learning and working, etc. While I wrote the book, I came across other words that were related to the historical content. For instance, heorþ wasn’t in my hoard until I started researching and writing about how to make bread in early medieval England.

There are lots of other words that didn’t make the book, but there is a second book coming! It will focus on animals and animal words.

The Wordhord started as a Word of the Day Twitter account, which is not just a worthy follow but part of an enthusiastic and wonderfully amusing community of Medievalists on twitter. What are some of your favorite Medievalist Twitter accounts? Do you think there’s a particular appeal that Medieval words, art, and culture has to an internet audience?

For medieval manuscript images there are @BLMedieval, @MarginaliaMS, @discarding_imgs, @red_loeb, @melibeus1, @sims_mss, and many others. If you want more Old English content, there are @digitalmappa and @thijsporck. @Medievalists shares articles on a lot of different topics. And there are many scholars on Twitter who share their fascinating work – the best way to find them is using the hashtag #medievaltwitter.

I think that people have been fascinated by the Middle Ages for a long time and that the internet has just provided another way to enjoy learning about this period. And because more libraries are digitizing and sharing their manuscripts, there’s a lot more material available to look at, even without a library membership.

Lots of people’s knowledge of OE begins and ends with Beowulf—where should people start if they want to read more? What do you recommend for the curious (but not necessarily scholarly) reader?

The Word Exchange is a book of Old English poems in translation with each poem translated by a different poet, so that gives you some nice variety. The tenth-century Exeter Book riddles are fascinating (and often humorous), and these are on theriddleages.com, with translations, commentaries and proposed solutions. (The Exeter Book gives no solutions, so scholars can only make guesses.)

What Old English words do you wish would make a comeback?

There are a couple of animal words that I just love. Hreaðe-mus literally means “adorned mouse” and it is Old English for bat (a mouse adorned with wings). Gongel-wæfre literally means “walking-weaver” and it’s an Old English word for a spider.

There are also words that describe things so well that I wish we still used. Uht-cearu is pre-dawn anxiety, the worries that keep you awake at three AM. A morgen-drenc (meaning “morning-drink”) has healing (perhaps even magical) properties, which I think is a great way to describe coffee.

How can you get the Old English word of the day?

You can subscribe for daily emails at oldenglishwordhord.com or follow @OEWordhord (Twitter), @oewordhord (Facebook) and @oldenglishwordhord (Instagram). And if you have an iOS device you can download the free Old English Wordhord app (bit.ly/WordhordApp).