It’s one of our favorite days of the year: National Cat Day! Not only do we think kitties are just purrfect, we also love those whiskery words and feline phrases. Here’s a brief history of cat idioms and where they might come from.

16th century: Kings, care, and the cover of darkness

Cats have minced their way through many a proverb since at least the 1500s. A cat may look at a king is an early one. From about 1546, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), it means that there are certain things an inferior might do even in the presence of a superior.

Care killed the cat is from around the same time. Here “care” means worry or sorrow, says The Phrase Finder, so the proverb seems to mean that worry or sorrow would kill even a creature with nine lives — in other words, a cat. Curiosity killed the cat came later, around 1898.

The saying that all cats are gray (in the dark) is from about 1550, says the OED, and means that under certain circumstances, distinguishing qualities between people or things become unimportant.

17th century: Raining and swinging

The phrase to rain cats and dogs goes all the way back to at least 1661, says the OED. The Online Etymology Dictionary says it probably comes from cat-and-dog meaning inharmonious.

If you live a tiny space, you could say there’s not enough room to swing a cat, which is from about 1665, again according to the OED.

18th century: Bags, bells, and beaming

Revealed a secret? Then you’ve let the cat out of the bag. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, this phrase is attested from 1760 and probably comes from the French expression acheter chat en poche, “buy a cat in a bag.” This is in contrast with the saying buy a pig in a poke, that is to buy something without looking at it or knowing its true value. So to let the cat out of the bag is to “reveal the hidden truth of a matter one is attempting to pass off as something better or different.”

To bell the cat, meaning to take on a perilous task on behalf of a group, may come from a late 14th century fable about mice belling a cat, says the Online Etymology Dictionary. And while we might think the saying to grin like a Cheshire cat comes from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which was published in 1865, the saying is attested from 1770. However, what the connection is between the English county of Cheshire, grinning, and cats is unclear.

19th century: Skin, tongues, cowards, and copiers

Poor kitties. So far they’ve been killed by both care and curiosity, swung, and put in bags. By the 1840s, there was also more than one way to skin them, which of course means there’s more than one way to do something.

Cat got your tongue? you might say to someone on the quiet side. While the OED’s earliest citation is from 1911, The Phrase Finder’s is from 1859. However, why a cat would have one’s tongue is unclear.

By 1871, a timid person might be called a fraidy-cat, perhaps from the puss’s practice of leaping and scattering when startled. The term scaredy-cat was scared up a bit later: in 1906. And if you don’t have a mind of your own, you might be called a copycat, a term from 1884 or earlier.

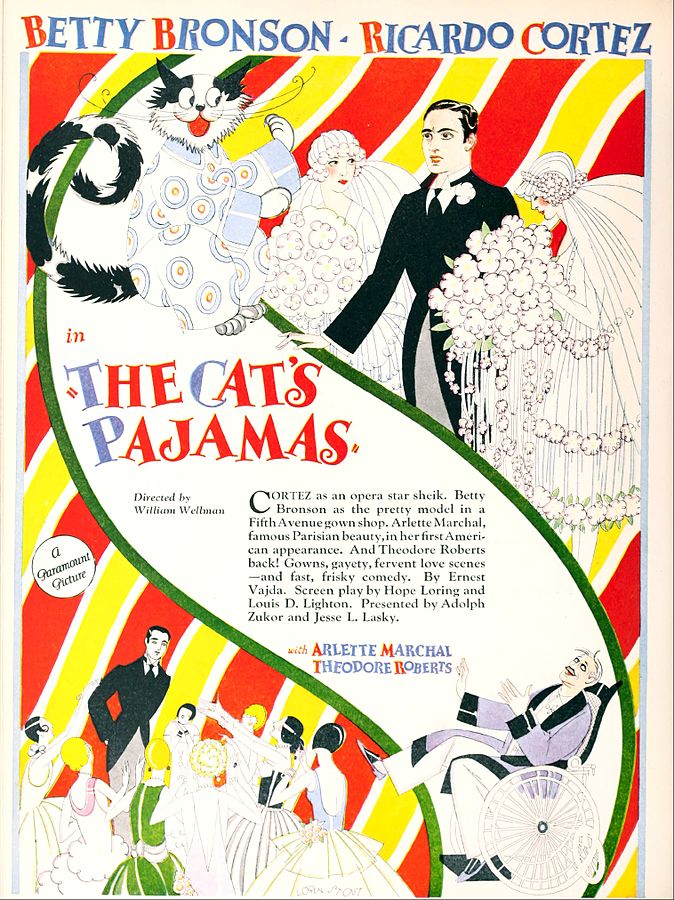

1920s: Cat phrases are the bee’s knees

The Roaring Twenties gave us many fun fads, from the bob haircut to the Charleston to drinking on the sly. Another one was animal-themed nonsense phrases that described something excellent. As per the OED, cat’s meow is from 1921 while cat’s whiskers and cat’s pajamas are from 1923 and 1925, respectively. An non-excellent cat phrase from 1928 is to look or feel like something the cat dragged in.

1980s: Herding and more swinging

The phrase herding cats — trying to control something unwieldy — is from the mid-1980s. The OED’s earliest citation is from 1986 while other sources mention a slightly earlier one from 1985. The saying was made even more popular by a commercial from 2000.

Reminiscent of the 17th-century phrase not enough room to swing a cat is the more macabre can’t swing a dead cat without hitting something there are too many of. From a Jan. 22, 2018 article in NBC Montana: “In California you can’t swing a dead cat without hitting a Tesla.” World Wide Words says the phrase is from the late 1980s.

Want more animal words and phrases? Check out our posts on regional slang terms for dogs, linguistic (and literal) animal blends, and how to speak rabbit.