Today we are proud to announce the first release of SwaggerSocket, a REST over WebSocket Protocol.

Why?

REST is a style of software architecture which is almost always delivered over HTTP. It powers most of the World Wide Web and has enabled the rapid construction of APIs–it has allowed developers to easily integrate many complex services with their applications. It has been truly transformational over the last 10 years.

The problem is, HTTP is a chatty, synchronous communication protocol based entirely on “request/response”. That is, there is no easy way to open continuous communication between a client and a server. You have to “ask a question” and wait for the response. There have been a number of techniques developed to make HTTP less “chatty”–these include long-polling, Comet, HTTP streaming and recently, web sockets. While REST over HTTP has transformed “over-the-internet” communication, it is usually a poor choice for high-throughput or asynchronous communication. For example, most software programs do not communicate to their databases over HTTP. It’s typically too slow because of HTTP overhead.

Websockets, however, have provided a new type of communication fabric for the Internet. By being full duplex–meaning, a program can both ask a question and listen to a response simultaneously–and truly asynchronous, they can not only speed up software by “doing more things at once”, they can provide a more efficient pipe to send information through.

The challenge, though, is that WebSockets are simply a protocol for communication–they do not define the structure itself. All the goodness that came with REST (structure, human readability, self-description) is abandoned for the sake of efficiency. This is why Wordnik created SwaggerSocket!

How Does SwaggerSocket Work?

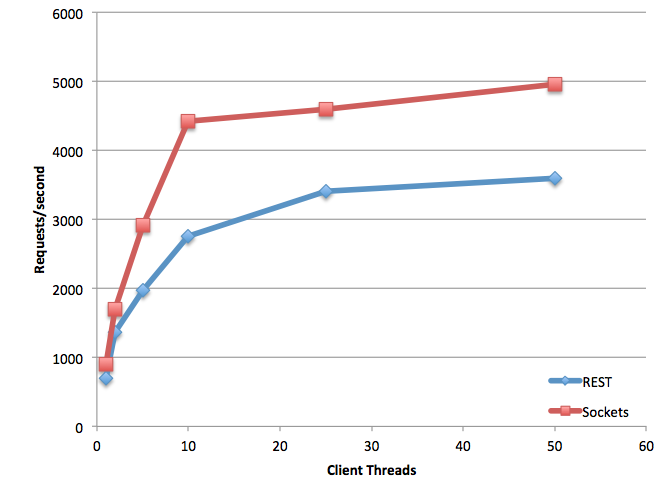

First, let’s see how SwaggerSocket improves performance over a typical REST implementation:

Note this is a simple, sample of REST over WebSocket performance. A follow-up post will go into the gory details of testing methodology and scenarios, as well as to the theoretical why performance will be better. For the record, the above graph was produced on an Amazon M1.Large EC2 server.

The REST resource used for testing looks like this simple Swagger annotated resource:

object Counter {

@volatile var count: Double = 0

def increment: Double = { count += 1 count } }

trait TestResource {

@GET

@Path("/simpleFetch")

@ApiOperation(value = "Simple fetch method", notes = "",

responseClass = "com.wordnik.demo.resources.ApiResponse")

@ApiErrors(Array( new ApiError(code = 400, reason = "Bad request")))

def getById(): Response = {

Counter.increment Response.ok.entity(new ApiResponse(200, "success")).build }

}

@Path("/test.json")

@Api(value = "/test", description = "Test resource")

@Produces(Array("application/json"))

class TestResourceJSON extends Help

with ProfileEndpointTrait

with TestResource

On the client we incrementally hit the resource by either using the Jersey REST Client (for REST) or using SwaggerSocket Scala Client for WebSocket (based on AHC). As you can see, SwaggerSocket can easily outperform normal REST requests. To keep the comparison fair, the SwaggerSocket client used is blocking waiting for the response. This is the same way that a typical REST client would behave–using an asynchronous programming style will not only be faster for the client, but it allows the server to degrade more gracefully under load as well as perform batch operations transparently.

Introducing the SwaggerSocket Protocol

The SwaggerSocket Protocol is:

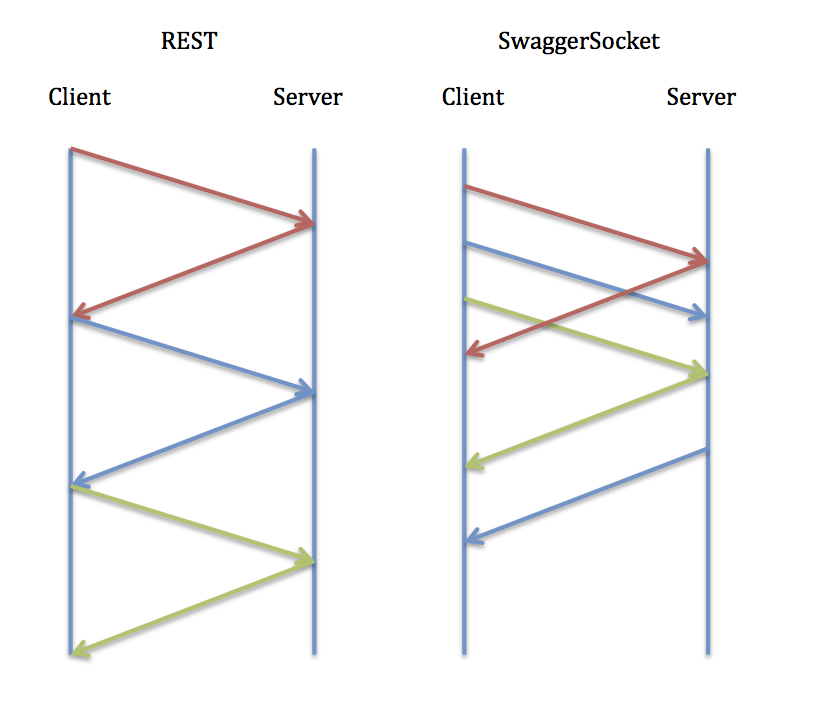

- Pipelined: unlike the HTTP protocol (unless HTTP Pipelining is used), when you open a connection and send a request, you don’t have to wait for the response to be arrive before being allowed to send another request. SwaggerSocket requests can be sent without waiting for the corresponding responses. Unlike HTTP Pipelining (which is not supported by all browsers), SwaggerSocket works with any browser supporting WebSocket.

- Transparent: The SwaggerSocket Protocol implementation from Wordnik is transparent and doesn’t require modification of existing applications. For example, any existing JAX RS/Jersey applications can work with no changes. For the client side, an application can either use the SwaggerSocket’s Javascript library, SwaggerSocket’s Scala library or open WebSocket and manipulate the protocol object.

- Asynchronous: The SwaggerSocket Protocol is fully asynchronous. A client can send several requests without waiting or blocking for the response. The server will asynchronously process the requests and send responses asynchronously.

- Simple: The SwaggerSocket Protocol uses JSON for encoding the requests and responses. This makes the protocol easy to understand and to implement.

How does it work?

The SwaggerSocket Protocol uses JSON to pass information between clients and servers via a WebSocket connection. A client first connect to the server and wait for some authorization token. On success, the client can start sending requests and gets responses asynchronously.

Software Languages Supported

SwaggerSocket as a protocol can be implemented in nearly all programming languages. The Wordnik implementation currently supports Java, Scala, Groovy and JRuby for the server components, and ships with a Scala and Javascript client library. The swagger-codegen will be updated to support SwaggerSocket for other clients

How can I try SwaggerSocket?

The easiest way to try SwaggerSocket is to go to our Github site and download one of the sample and read our Quick Start. Details of the SwaggerSocket Protocol can be read here.

Getting involved

To get involved with SwaggerSocket, subscribe to our mailing list or follow us on Twitter or fork us on Github!