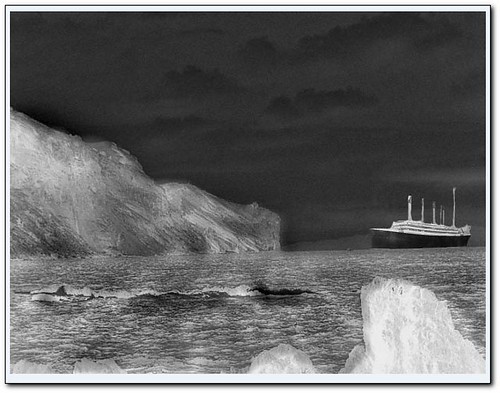

One hundred years ago today, the RMS Titanic set sail on its first and only voyage, and thanks to James Cameron, most of us know the story of the ship and its fateful meeting with a big block of ice. But how about the story behind those titanic words?

The RMS Titanic was a passenger superliner, an ocean liner “of over 10,000 gross tons.” In the 19th century, the term was coined “when ocean liners were rapidly increasing in size and speed.” In the first half of the 20th century, superliners became “the primary means of intercontinental travel … as passengers favoured large, fast ships.”

Why RMS? That stands for Royal Mail Ship or Service, “used for seagoing vessels that carry mail under contract to the British Royal Mail.” As opposed is HMS, which stands for “Her (or His) Majesty’s Ship,” a designated British warship. As for titanic, it means “of, pertaining to, or characteristic of the Titans; hence, enormous in size, strength, or degree; gigantic; superhuman; huge; vast.” Titan may come from the Greek tito, “sun, day.”

How about that iceberg? An iceberg (from the Middle Dutch ijsbergh, “ice mountain”) is part of a glacier (from an Old French word meaning “cold place”) that has broken off by a process called calving. Calving is the same term used for when animals such as cows, whales, or seals give birth to calves. Thus, that broken piece of ice is often referred to as a calf.

Icebergs come in different sizes. Smallest is brash ice, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, fragments of ice “less than 2 meters big,” so-called perhaps from the “brittle” meaning of brash. Next is the growler, measuring less than one meter high and less than five meters long. Growlers, according to Mariana Gosnell in her book, Ice, “got their name from the sound they make when. . .they plunge deeper into the water, sucking and growling.” A bergy bit is slightly larger than a growler, while the iceberg that sunk the Titanic seems to have been medium-sized.

When glacier ice melts, it makes bergy seltzer, also called ice sizzle, “a crackling or sizzling similar to that made by soft drinks or seltzer water,” and “made as air bubbles formed at many atmospheres of pressure are released.”

Since glaciers are formed from snow “falling on the higher parts of those mountain-ranges which are above the snow-line,” they are freshwater, unlike floe-bergs, “ice resulting from the freezing of the surface-water of the ocean.” Floe probably comes from the Norwegian flo, “layer.” A cloud-berg is “a mountainous mass of cloud which looks like an iceberg on the distant horizon.”

Typically only “one-ninth of the volume of an iceberg is above water,” hence the phrase, tip of the iceberg, “a small evident part or aspect of something largely hidden.” The phrase may have originated in the mid-1950s. Iceberg lettuce is “a lettuce cultivar noted for its crunchiness; the most familiar of all lettuces sold in the United States.” The name attests to 1893 (despite claims that Fresh Direct creator Bruce Church invented the phrase in 1926).

Glacionatant means “belonging to or affected by floating ice, as distinguished from ice moving on land,” as in “The Titanic’s sinking was glacionatant.” The word comes from the Latin glacies, “ice,” plus natare, “to swim.” Naufragous means “causing shipwreck,” as in, “The iceberg was naufragous.” The word may come from the Greek naus, “ship,” and the Latin fragmentum, “a fragment, remnant.” Naufragiate means to cause shipwreck, while naufrage refers to shipwreck itself.

Jetsam (from the Middle English jetteson, “a throwing overboard“) is that which has been “thrown overboard to lighten a ship in distress.” Flotsam (from the Old French floter, “to float“) is “wreckage or cargo that remains afloat after a ship has sunk.” Ligan or lagan (possibly from the Old Norse lagu, “law”) is “anything sunk in the sea, but tied to a support at the surface, as a cork or buoy, in order that it may be recovered.” Have a dispute about these items? Enlist a scrutator, “a bailiff appointed to protect the king’s water-rights, as flotsam, jetsam, and wrecks.” Scrutator comes from the Latin scrūtinium, “inquiry.”

Finally, be sure to check out these lists of glacial effects, ice phenomena, and famous ships.

Now that you know the story behind some titanic words, we hope you feel like the king of the world.

[Photo: “Her Maiden Voyage,” CC BY 2.0 by Patrick McConahay]