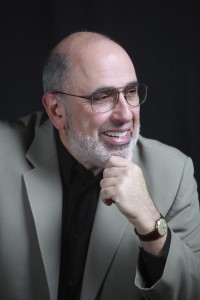

In the latest of our series of interviews with professional namers, today we speak with Steve Rivkin.

Steve is the founder of Rivkin & Associates LLC, a marketing and communications consultancy that specializes in naming. He is the co-author of The Making of a Name (Oxford University Press) – described by its publisher as “the definitive work on names and naming” – and has been called “America’s leading nameologist” by Asian Brand News.

How did you get started in the naming business?

It was an outgrowth of my consulting work in developing and then executing marketing strategies. The need for a new name was an integral part of the majority of these projects, and I was dissatisfied with the methods and narrow focus I saw.

Any new name, I believe, should embrace several disciplines. First and foremost, a new name must have a strong positioning orientation to help differentiate the brand. It also should have a strong consumer sensibility, and it should have a realistic basis in linguistics.

To do this requires seasoned professionals with hands-on business experience in marketing and communications. There are no rookies or academic linguists on our team, which is a common practice at the big naming factories.

What types of customers and clients do you work with?

All sorts. We have naming clients in the food, healthcare, communications, financial services, and technology sectors.

Please describe the naming process. Do you usually start with ideas, or do you find your customers often have their own ideas already?

We start with a clear briefing from the client on their objectives, likes and dislikes regarding a new name.

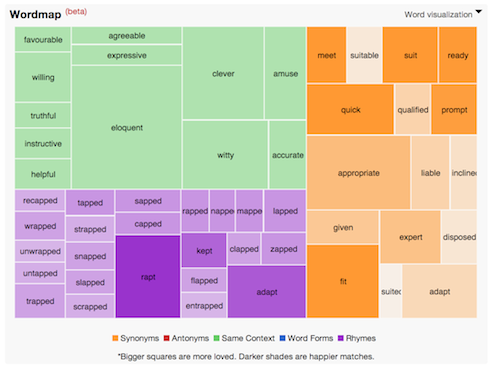

Next, we develop a specific vocabulary list about the client’s business, product or service. That list is then enlarged by adding roots, synonyms, analogues, idioms, collocations, and translations, to create the building blocks we need.

Then we employ a series of techniques that we know will generate large numbers of possible names: construction of new words (neologisms) from recognizable roots, by using word fusions, suffixes joined to building-block terms, and other methods; existing terms or words used in new ways, such as adapted metaphors; compressions or contractions of existing words and phrases; application of imagery and symbolism; and other techniques and inspirations.

What are some mistakes you’ve seen companies make in terms of naming?

Devouring their own. Alpo Cat Food, A-1 Poultry Sauce, V8 Fusion Plus Tea, Tanqueray Vodka. These marketers have stretched the original meaning of their names past recognition – or believability.

Yes, all brand names are elastic, to some extent. Consider the brand ESPN. It started out in 1997 as a single cable channel, but has since mushroomed into half a dozen other channels, two radio channels, Internet access, and a print magazine – all built around the concept of sports coverage and commentary. But note the core concept behind everything ESPN does. A name can only be stretched to a certain point before it “snaps” in the consumer’s mind and no longer stands for a clear concept.

Another common mistake: the impolite utterances that others have commented on, such as the shoe brands named Incubus (a demon) and Zyklon (a poison used by the Nazis). Ikea has a catalog offering for a workbench named Fartfull. (I’m guessing that moniker is attractive in Swedish.)

Foreign language stumbles are particularly embarrassing. Pajero, an SUV from Mitsubishi. (You can look it up in any Spanish dictionary: “One who masturbates; a wanker.”) Country Mist, a cosmetic product that Estee Lauder shipped to Germany. (In German, “mist” means “manure.”) Burrada, used to identify a frozen Mexican food entrée. (Burrada translates as “a stupid deed” or “ big mistake.”)

What are some names that you particularly like?

You know I’m going to embrace our creations for clients. Here are a few of them: Behold single-vision lens, Premio Italian sausages, Trueste perfume, Celsia Technologies, Global Impact for charitable assistance.

I’m also drawn to names that are unexpected combinations of language, because they engage the brain on several levels. They’re surprising, meaningful and playful – all at the same time. Examples: Geek Squad. DreamWorks, which combines the magic of movies with an old industrial term. Zany Brainy, the educational toy store. Sky Harbor, the name of the airport in Phoenix.

And I applaud companies which do not blur the distinctions among their brands. For instance, American Honda Motor Company applied its mid-range Honda brand name to a lineup of vehicles – Civic, Accord, CR-V. But as Honda climbed the ladder of performance, styling and luxury, it realized it could not “stretch” the Honda brand indefinitely – and the upmarket Acura brand was born, with a completely separate identity. (You have to search long and hard in Acura materials to find any references to Honda.)

What are some trends you’d sooner see die off?

One: The fascination with what I call techno-babble. Or we could call it geek-speak. Names such as (and I’m not making these up) @Climax, 1-4-@LL, 160 over 90, Design VoX, mmO2, and $Cashnet$.

Another: The epidemic of me-tooism of “Ameri-something” names: Americare, Americone, Amerideck, Ameridial, Amerihealth, Amerilink, Amerimark, Ameripride – enough!

And one more sin in naming: Thou shalt not prepare alphabet soup. “JCP&L, a GPU Company.” How that’s for dead-end communication? Or these recent adventures into anonymity from the Fortune 500: AES, BB&T, KBR, URS, SLM. That’s a total of $35 billion in corporate revenues, all cloaked in an invisible, all-initial shield.

![[ T ] John Tenniel - Alice Through the Looking-Glass (1871)](http://farm6.staticflickr.com/5212/5485576189_14061e9d8b.jpg)