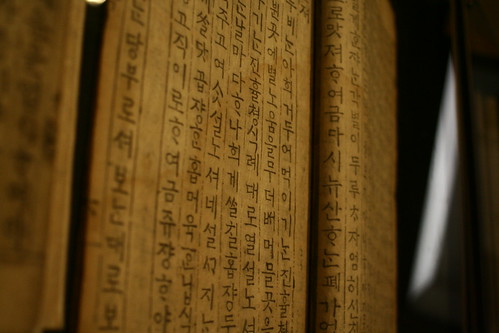

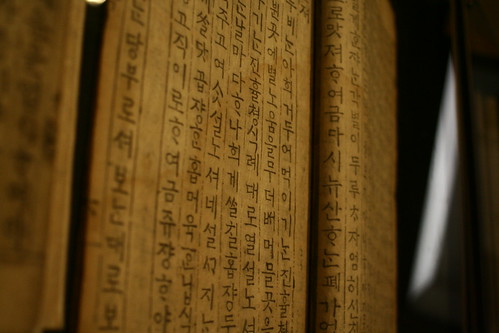

Hangul by Andrew 鐘, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by Andrew 鐘]

This Sunday, October 9, is Hangul Day, the yearly commemoration of “the invention and proclamation of [the] native alphabet of the Korean language.”

Prior to the establishment of Hangul (which translates as “great writing”) in 1446 by King Sejong the Great, according to this Language Log post:

the Korean language was rarely written at all. The written language used in Korea was Classical Chinese. The combination of the use of a foreign language with the large amount of memorization required to learn thousands of Chinese characters meant that only a small elite were literate, overwhelmingly men from aristocratic families. The great majority of people were illiterate.

Written Chinese (or hanzi) is semanto-phonetic, says Omniglot, an excellent source on writing systems, and uses pictograms, logograms, and ideograms. Other examples of semanto-phonetic writing systems are ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and Mayan.

Detail of heiroglyphics by dustinpsmith, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by dustinpsmith]

Hangul, however, is alphabetic, using each letter to represent a consonant or vowel. Other alphabetic writing systems are Latin, Roman, and Cyrillic, “which have been adapted to write numerous languages,” including modern English, and futhork, “the Old English runic alphabet.” Runes are letters or characters “used by the peoples of northern Europe from an early period to the eleventh century. . .believed to be derived from a Greek source.” Greek is the first alphabetic system to use vowels.

Cyrillic McDonalds by david.orban, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by david.orban]

Ogham is an alphabetic writing system made up “of 20 letters used by the ancient Irish and some other Celts in the British islands.” Tifinagh is “an alphabetic script used by some Berber peoples, notably the Tuareg,” and is “thought to have derived from ancient Berber script.” Avestan is “the script in which the ancient Persian language of the Avesta is written,” while Glagolitic is “the oldest known Slavonic alphabet, designed around 862–863 CE by Saint Cyril in order to translate the Bible and other texts into Old Church Slavonic.”

DSCF0041 by VicWJ, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by VicWJ]

More examples of ogham.

Hangul is sometimes wrongly considered a syllabary or phonetic writing system with “symbols representing sounds,” but it’s not, says Language Log, because it’s “completely analyzable at the segmental level” and “the groups into which the letters are formed do not correspond exactly to syllables.” Some syllabaries include kana, Japanese syllabic writing (literally “false name”), which is made up of two types: hiragana, “the cursive form of Japanese writing,” with hira meaning “plain, ordinary,” and katakana, an “angular kana used for writing foreign words or official documents, such as telegrams,” with kata meaning “one.” Chinese characters as used in Japanese are referred to as kanji, “Chinese characters.”

A Chinese semi-syllabary writing system is bopomofo or zhuyin fuhao:

a phonetic script used in dictionaries, children’s books, text books for people learning Chinese and in some newspapers and magazines to show the pronunciation of the characters. It is also used to show the Taiwanese pronunciation of characters and to write Taiwanese words for which no characters exist.

Zhuyin fuhao translates as “phonetic symbol,” while bopomofo are the first four letters of the system.

TC Keyboard by sanbeiji, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY-SA 2.0 by sanbeiji]

More examples of bopomofo.

Nüshu, which translates from Chinese as “women’s writing,” is “a syllabic script created and used exclusively by women in Jiangyong Prefecture, Hunan Province, China.” Omniglot goes on:

The women were forbidden formal education for many centuries and developed the Nüshu script in order to communicate with one another. They embroidered the script into cloth and wrote it in books and on paper fans.

Nüshu may have regained popularity recently due to the novel Snow Flower and the Secret Fan.

Abugidas or syllabic alphabets “consist of symbols for consonants and vowels,” with consonants each having “an inherent vowel which can be changed to another vowel or muted by means of diacritics.” In addition, “vowels can also be written with separate letters when they occur at the beginning of a word or on their own.” Abugidas include Devanagari, “used to write several Indian languages, mainly Sanskrit and Hindi,” and which was descended from the ancient brahmi; Gurmukhi, “designed for writing the Punjabi language”; and Ge’ez or Ethiopic, used to write several Ethiopian languages.

R0018642 by nozomiiqel, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by nozomiiqel]

More examples of Devanagari.

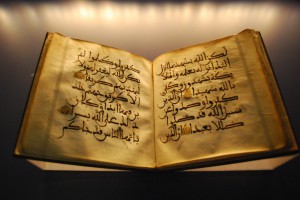

Abjads or consonant alphabets “represent consonants only, or consonants plus some vowels.” Abjads still in use are Arabic and Hebrew. Extinct abjads include Aramaic, Phoenician, and Samaritan.

Some writing systems still have yet to be deciphered, such as rongorongo, “an early glyphic writing system of Easter Island, written in reverse boustrophedon.” Boustrophedon is “a method of writing shown in early Greek inscriptions, in which the lines run alternately from right to left and from left to right, as the furrows made in plowing a field, the plow passing alternately backward and forward,” which you may remember from our post on writing.

Rongorongo tablet by christopherhu, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by christopherhu]

Alternative spelling systems are “designed to make it easier to learn how to write English.” These include the phonetic alphabet developed by Benjamin Franklin, and Shavian, “named after George Bernard Shaw” and devised as a result of a competition “to create a new writing system for English.”

Fictional alphabets are “writing systems used in books, films and computer games.” JRR Tolkien invented several for his Lord of the Rings books, including Cirth, Sarati, and Tengwar. Atlantean is “the language supposedly spoken by the inhabitants of Atlantis,” while Klingon is “an artificial language created by Marc Okrand, first appearing in a Star Trek episode in 1967.” Other notation systems include braille and shorthand, while some language-based communication systems include Morse code and semaphore.

Language Log suggests you celebrate Hangul Day with a drink such as “makkeolli, a kind of rice wine also known as 농주 nong-ju ‘farmer’s wine.'” May we also suggest this beautiful Hagul Day bento.

hangul day bento by gamene, on Flickr

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by gamene]

Happy 한글 Day!