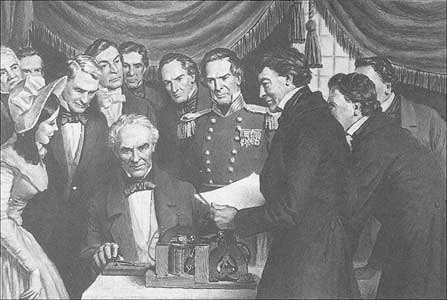

On this day in 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse sent the first public message over his invention, the telegraph. The message, “What hath God wrought?” was dispatched, says the Library of Congress, “over an experimental line from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore,” and “had been suggested to Morse by Annie Ellsworth, the young daughter of a friend.” Some proclaim today Morse Code Day, while others prefer April 27, Morse’s birthday. Either seems like a good time to celebrate telegraph language.

The word telegraph came about before the invention of the electric telegraph. In 1794, says the Online Etymology Dictionary, the telegraph was a “semaphore apparatus” invented in France, which translated literally as “that which writes at a distance.” In 1797, the word was applied for the first time to an “experimental electric telegraph.”

Wireless telegraphy, also known as spark-telegraphy, is “telegraphy by radio rather than by long-distance transmission lines.” The marconigraph was a wireless telegraph developed by Guglielmo Marconi, one of the earliest developers of long-distance radio, while to aerograph means “to communicate by means of wireless telegraph.” The marconi system uses Hertzian waves “in transmission and a coherer. . .as the receiving instrument.” A marconist practices marconism, “the art of wireless telegraphy according to the Marconi system.”

Morse code, a type of symbol-printing, was invented in part by Morse and expanded by Alfred Vail, a machinist and inventor. It uses dots and dashes to communicate, the dot, “the short sound or signal,” and the dash, “the long sound or signal.” The spoken representations of the dot and the dash are, respectively, dit and dah since they “more closely resemble the timing of the sounds.”

A prosign, or procedural signal, is “any of a set of special sequences in Morse code used as control characters and punctuation.” An example of a prosign is SOS, “an international distress signal, especially by ships and aircraft.” SOS, by the way, isn’t short for “save our ships” or “save our souls.” The letters were “chosen arbitrarily as being easy to transmit and difficult to mistake.” An alternative suggestion was C.Q.D., which may mean “come quickly, distress.” SOS “is the telegraphic distress signal only,” with the spoken equivalent being mayday.

Like all languages, Morse code has its own slang. Rag-chewing refers to a conversation that’s longer than usual, “generally a conversation extending about 30 minutes,” and comes from the idiom chew the rag. Achy digits? You might have morse finger, a “contraction of the finger following a traumatic inflammation of the joints excited by overuse in pressing the keys of the Morse telegraph.”

Umpty, an indefinite number, was “originally Morse code slang for ‘dash,’ influenced by association with numerals such as twenty, thirty, etc.” Thirty indicates “the last sheet, word, or line of copy or of a despatch,” while in the 20th century “jargon of journalism, it came to be a traditional sign-off signal and slang word for ‘the end.’” Seventy-three means “best regards” while eighty-eight means “hugs and kisses.” (The origins of these is unknown, as far as we can tell.) Check out even more telegraph and radio slang.

Then there are the non-telegraph words the telegraph gave us. For instance, while today we know a troubleshooter as “a worker whose job is to locate and eliminate sources of trouble, as in mechanical operations,” as well as “a mediator skilled in settling disputes especially of a diplomatic, political, or industrial nature,” it was originally “one who works on telegraph or telephone lines.”

Most of us have heard a rumor through the grapevine, but you may not know that grapevine is actually short for grapevine telegraph. World Wide Words says the phrase originated in the U.S. “sometime in the late 1840s or early 1850s,” providing “a wry comparison between the twisted stems of the grapevine and the straight lines of the then new electric telegraph marching across America.”

Unlike the electric telegraph, “the grapevine telegraph was by individual to individual, often garbling the facts or reporting untruths (so reflecting the gnarled and contorted stems of the grapevine), but likewise capable of transmitting vital messages quickly over distances.” It was during the Civil War that the phrase gained widespread popularity.

Those are the dits and dahs from us. Till next time, 73 and 88!