The first issue of The New York Times was published on this day in 1851, and to celebrate we’re taking look at a brief history of some of our favorite newspaper words and slang.

Before newspapers, there were government bulletins. The Acta Diurna or Daily Acts of ancient Rome were carved in metal or stone and posted in public places. In ancient China, tipao, news sheets produced by the government, were “handwritten on silk and read by government officials.”

In 16th century Venice, a monthly notice was published and sold for one gazeta, a small copper coin, which may be where we get gazette, another word for newspaper.

However, gazeta also means “little magpie,” so it’s unclear if we get the word from the paper’s “price or its association with the bird (typical of false chatter),” says the Online Etymology Dictionary. What we do know is that gazette predates the word newspaper by about 60 years.

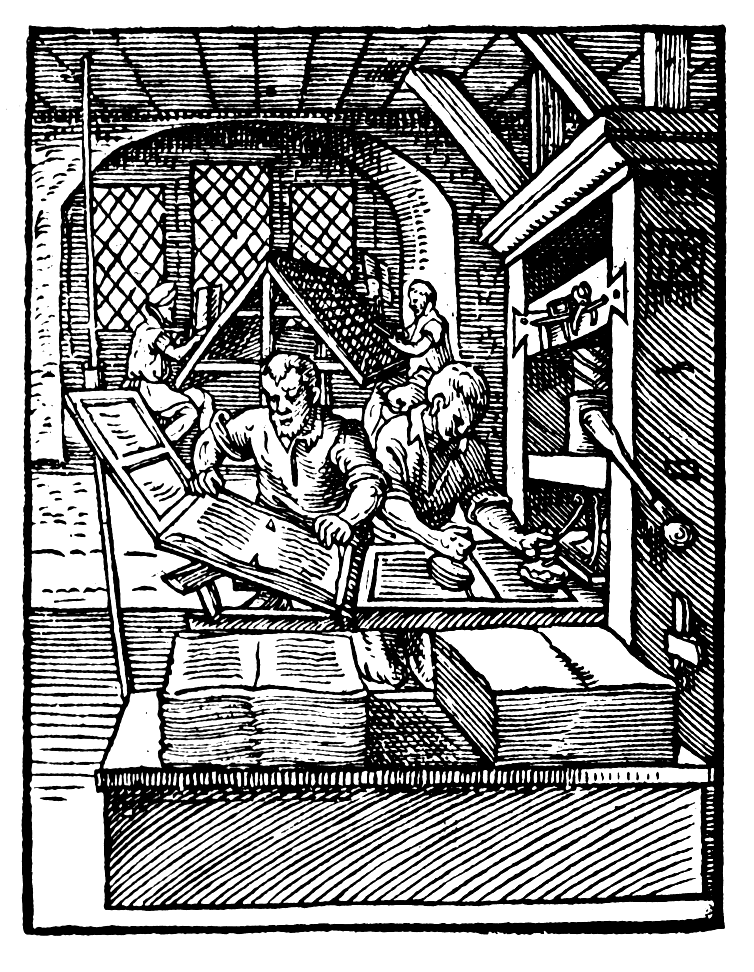

By 1649, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), newspapers, journals, and periodicals were collectively referred to as the press. This of course comes from printing press, which was invented in the 15th century and quickly gained popularity in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. By the late 1860s press came to refer to journalists in general, and to journalistic coverage by 1908: “Mr. Leaf. . .has not had a good press lately.”

Both newsman and journalist came about in the late 17th century, says the OED. By then what’s considered the first American newspaper was published in Boston, although “only one edition was published before the paper was suppressed by the colonial officials.” A few years later, a weekly called The Boston News-Letter “became the first continuously published newspaper in the colonies.”

By 1734, you could insult a newspaper by calling it a rag. Know where the bodies are buried? You could make a living as a death-hunter, “one who furnishes a newspaper with reports of deaths,” says the OED.

Reporters weren’t called reporters until about 1776, as per the OED. By 1810, if you were a writer for hire, you might be called a hack, and in the 1870s, a story you got before a competitor was called a beat or scoop.

By the late 19th century, competition betweens papers was fierce. Some resorted to keyhole journalism, says the OED, with “allusion to the action of eavesdropping or spying through a keyhole.”

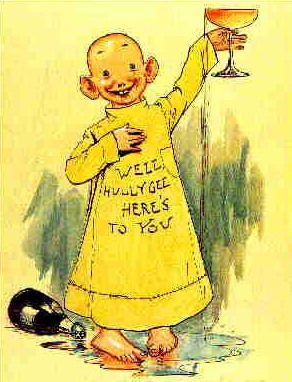

The term yellow journalism was coined around 1898 during the peak of the “circulation battles” between Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. Yellow journalism is “journalism that exploits, distorts, or exaggerates the news to create sensations and attract readers,” and comes from “the use of yellow ink in printing ‘Yellow Kid,’ a cartoon strip in the New York World.”

Pulitzer and Heart’s sensationalistic exploits were even blamed for the United States’ entry into the Spanish-American War, although historians have noted that “yellow journalism was largely confined to New York City, and that newspapers in the rest of the country did not follow their lead.”

In 1901, the term tabloid was being used to describe newspapers that gave stories in condensed form, “usually with illustrated, often sensational material.” The word tabloid was originally a trademark referring to a “small tablet of medicine,” says the Online Etymology Dictionary, and eventually came to refer to “a compressed form or dose of anything.”

Lead meaning the “introductory portion of a news story” is from around 1912. The spelling didn’t change to lede until 1965, perhaps “to distinguish this sense from other possible meanings of the written word,” such as the molten lead “used in typesetting machines.” The term bury the lead, beginning a story with secondary information and revealing the important points later, is from 1977, says the OED.

Lonely-hearts referring to lonely-hearts columns originated in the early 1930s while agony aunt, a British English term for the writer of an advice column, is from 1974. In 1950, if you wrote a story of “exaggerating praise,” you’d be writing a puff piece. Paparazzi, photographers who “pursue celebrities and attempt to obtain candid photographs,” comes from the “surname of the freelance photographer in Federico Fellini’s 1959 film ‘La Dolce Vita.’”

Supermarket tabloids arose in the 1960s, says Vanity Fair. Neighborhood newsstands and family-owned shops were closing as supermarket chains opened up. Generoso Pope, Jr., the creator of The National Enquirer, perhaps the most famous (or infamous) supermarket tabloid, “understood that the only way tabloids could thrive as their urban habitat declined was by being sold in supermarkets.”

We’re uncertain as to when the term supermarket tabloid originated exactly. The earliest citation we found was from 1980, and Google Ngrams shows its usage beginning around the same time. However, if anyone can antedate us, please do.

In 1971 journalist Hunter S. Thompson coined the term gonzo journalism, a kind of experimental journalism in “which facts are deemed to be less important than perceived underlying truth (especially where deliberately altered consciousness is involved).”

Such journalism could be full of factoids, which contrary to popular belief aren’t bite-sized facts but “unverified or inaccurate information that is presented in the press as factual, often as part of a publicity effort, and that is then accepted as true because of frequent repetition.” The word was coined by writer Norman Mailer in 1973.

Gotcha journalism, “journalism that seeks only to catch public figures in embarrassing or scandalous situations,” says Word Spy. The earliest citation is from 1988. (The gotcharazzi, in case you were wondering, are paparazzi who may say “Gotcha!” when photographing someone in an embarrassing situation.)

The charticle, an article that mainly consists of a chart or graph, is from 1996, while listicle, an article consisting of a list, is newer, from 2003 and apparently coined by a Gawker writer, according to researcher Barry Popik.

Red-top, a tabloid newspaper in the UK, is from 1996, and refers to the red banners often used by such papers. A marmalade dropper is “highly stunning information” that would, presumably, cause one to drop one’s marmalade. Word Spy says the term “has appeared almost exclusively in British newspapers and magazines” and originated around 1995.

A dead donkey is “a news item of no real significance, usually of whimsical or sentimental nature, placed at the end of a news bulletin or in a newspaper as filler.” Drop the Dead Donkey was a 1990s British television comedy set in a TV news company. It seems the term dead donkey comes from the title of the show.

Finally, churnalism, journalism that uses “ready-made press release material copied wholesale,” is from 2001, says Word Spy.

What are some of your favorite journalistic slang terms?

[Photo: “New York Times Building, NYC,” CC BY 2.0 by Alexander Torrenegra]

[Photo: “Workers at a printing press,” Public Domain]

[Photo: “The Yellow Kid,” Public Domain]

[Photo: “Tabloid Rack,” CC BY 2.0 by Paulo Ordoveza]