Your doctor just broke the news to you: you have a bad case of rhinorrhea. Not only that, you’ve a touch of oscitancy and a bit of sudation too.

Prognosis? You have a runny nose, you’re yawning, and you’re sweaty. All of which adds up to, while not exactly a pretty picture, nothing too serious.

Here are 10 more conditions that sound more serious than they actually are.

borborygmus

“Wind is like the human breath, rain like secretions, and thunder like borborygmus.”

Ch’ung Wang, Lun-hêng: Philosophical essays of Wang Chʻung, 1907

Borborygmus is the sound of a rumbling tummy caused by gas. The word comes from the Greek borboryzein, “to have a rumbling in the bowels,” and is imitative in origin.

ephelides

“Medically known as ephelides, freckles are usually an inherited trait in families with blond or red hair and fair skin.”

Joan Liebmann-Smith, PhD and Jacqueline Egan, “Using Your 5 Senses to Make Sense of Your Baby’s Body Signs,” The Huffington Post, July 5, 2010

The ominous-sounding ephelides, Greek in origin, are more commonly known as freckles. Lentigo is another word for freckle and comes from the Latin lens, lent-, or “lentil.”

eructation

“Mr. P. is sullen, and seems to mistake an eructation for the breaking of wind backwards.”

Tobias Smollett, The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle, 1751

Eructation is a fancy way of saying “an instance of belching.” It comes from the Latin eructare, which means — you guessed it — “to belch.”

A fancy way of saying “an instance of farting,” in case you were wondering, is flatus. Flatus comes from the Latin word for “wind,” which also gives us flatulent.

horripilation

“The clergyman prayed aloud, when in a few moments, piercing shrieks were heard issuing from the oven. The whole company were in a state of horripilation.”

John Roussel, The Silver Lining, 1894

Horripilation is “the bristling of the body hair, as from fear or cold,” more commonly known as goose bumps, goose pimples, or gooseflesh. Horripilation comes from the Latin horripilare, where horrere means “to tremble” and pilare means “to grow hair.”

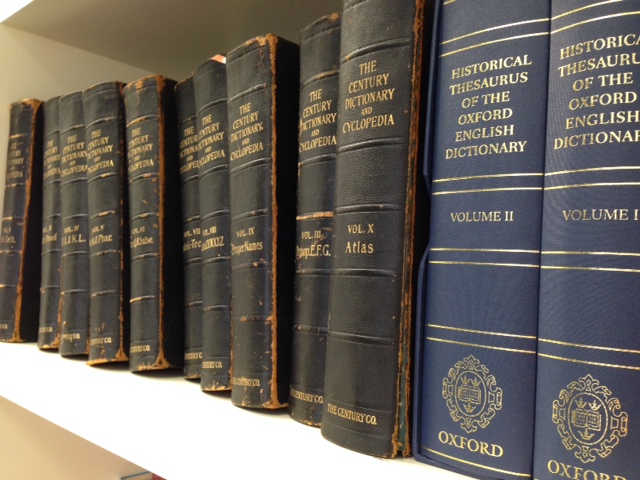

Of all the goose terms, gooseflesh — named of course for its resemblance to that of a plucked goose — is the oldest, originating around 1834, says the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Goose pimples came about around 1889 and goose bumps in 1933.

Goosebumps is also the name of a popular children’s horror series of books by R.L. Stine.

lacrimation

“For those of you unfamiliar with the makeover episode of America’s Next Top Model, know that it typically brings out tears, and I’m talking Niagara-like lacrimation.”

Disgrasion, “The ‘Ethnically Ambiguous’ Are So Last Season,” The Huffington Post, October 27, 2008

Lacrimation is “the secretion of tears, especially in excess,” otherwise known as crying. The word comes from the Latin lacrimare, “to weep.”

onychophagy

“M. Bertillon now tells us that biting the nails is a sign of degeneracy and gives it the hard name of ‘onychophagy.’”

The American Homoeopathist, Volume 19, 1893

Onychophagy is the habit of biting one’s nails. The word ultimately from the Greek onux, “claw, nail,” and phagos, “eater.” Onux also gives us onyx while phagos can be found in words like esophagus.

pandiculation

“If you’ve observed th’ awakened cat

Or one just risen from meditation —

She’ll stretch tremendously — well that

Is what is called ‘pandiculation.’”

George W. E. Daniels, “Pandiculation,” Medical Pickwick, Volume 7, 1921

Pandiculation is the act of stretching accompanied by yawning. The word ultimately comes from the Latin pandere, “to stretch.”

singultus

“Hiccups, more officially referred to as singultus (from the Latin, ‘to catch your breath while sobbing’), are repeated, spasmodic contractions of the diaphragm causing a quick inhalation that is then cut short by an involuntary closing of the glottis.”

Lisa Sanders, “A Serious Case of the Hiccups,” The New York Times, September 25, 2011

There are many “cures” for singultus, including drinking a glass of water upside-down, being scared, and placing sugar under the tongue. The record for longest bout of hiccups belongs to Charles Osborne, who hiccuped from 1922 to 1990.

The word hiccup is imitative in origin. An earlier form is hickop, which seems to be an alteration of the older hicket or hyckock. The Online Etymology Dictionary says that an Old English word for hiccup was ælfsogoða, “elf hiccup,” which was “so called because hiccups were thought to be caused by elves.”

Hiccough, according to the OED, was a later spelling of hiccup, “apparently under the erroneous impression that the second syllable was cough.” This spelling, the OED suggests, “ought to be abandoned as a mere error.”

sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia

“No one really knows why, but scientists think that stabbed-in-the-forehead feeling (sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia) occurs when the temperature of your palate doesn’t have time to normalize between spoonfuls of flavored ice.”

“How To: Land a Plane, Cure Brain Freeze, Get on Reality TV,” WIRED Magazine, May 19, 2008

No, it’s not a tumor. Sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia, more commonly known as ice-cream headache or brain freeze, happens when you eat cold things, like ice cream, too quickly.

Sphenopalatine refers to “the sphenoid bone and the palate,” in other words the roof of your mouth, while ganglioneuralgiarefers means nerve pain, or neuralgia, of the ganglion, “a group of nerve cells forming a nerve center, especially one located outside the brain or spinal cord.”

Ice-cream headache, a temporary condition, may be remedied in a number of simple ways.

sternutation

“Prometheus was the that wisht well to the sneezer, when the man, which he had made of clay, fell a fit of sternutation, upon the of that celestial fire which he stole the sun.”

William Carew Hazlitt, Faiths and Folklore, 1905

While a sternutation may sound like a tough talking to, it actually refers to a sneeze. The word comes from the Latin sternuere, “to sneeze.”

Sneeze, in case you were wondering, comes from the Old English fneosan, “to snort, sneeze.” Fn-, says the Online Etymology Dictionary, might have been misread has sn-, or else fnese was reduced to nese, and sneeze was “a ‘strengthened form’ of this, ‘assisted by its phonetic appropriateness.’” In other words, the word sneeze kind of sounds like the act of sneezing.

For even more harmless yet serious-sounding conditions, check out this list.

[Photo: “Blowing my nose,” CC BY 2.0 by superhua]

[Photo: “Andy at the Getty,” CC BY 2.0 by Kevin Dooley]

[Photo: “DSC_4804,” CC BY 2.0 by yoppy]

[Photo: “Ice Cream Headache?” CC BY 2.0 by Jereme Rauckman]