Welcome to the latest installment of “Five words from …” our series which highlights interesting words from interesting books!

The hottest Matrix of 2021 had nothing to do with white rabbits, red pills, or Keanu Reeves. This Matrix, Lauren Groff’s latest novel, tells the story of Marie de France as she progresses from ungainly orphan to powerful abbess in 12th-century England.

Colewort

“The coleworts are the size of three-month babies.”

Colewort, or cole, is the medieval ancestor of the Brassica oleracea species of vegetables, which today encompasses cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, collard greens, and brussels sprouts. Although the colewort of the twelfth century was smaller and more loose-leafed than its contemporary cultivars, it survives today in the word coleslaw.

Proper

“Temporale, the proper of time, the cycle of Christmas, the cycle of Easter. Sanctorale, the proper of the saints.”

Proper as a noun (not to be confused with a proper noun) is an ecclesiastical term that refers to the Catholic liturgical calendar: the proper is the portion of the liturgy that corresponds to each season or occasion. The Temporale is the proper of time because it consists of moveable feasts like Easter; the Sanctorale is the cycle of holy days with fixed dates, like Saints’ days and Christmas.

Monocerous

“Marie has become a great old monocerous. Hide of iron, single vicious horn, or so she hears.”

Monocerous (more commonly spelled monoceros or monocerus) comes from the Greek roots “monos”, single, and “keros,” horn, making it an etymological sibling to unicorn, which has the same roots, but in Latin. Depending on the context, monocerous can either be a synonym of unicorn or refer to a similar, but related creature. Monocerous far predates its Latin synonym, though: the creature is mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, where he described it as having “the head of the stag, the feet of the elephant, and the tail of the boar… and has a single black horn, which projects from the middle of its forehead, two cubits in length.”

Today, the word survives in the scientific name for the narwhal, Monodon monoceros.

Virago

“The abbess is not unlike a freemartin, that strange genre of virago ox not one thing or the other but both at the same time.”

Groff uses the word virago several times to describe her protagonist, including in Marie’s own thoughts of herself. Virago, literally a woman who behaves like or has the bearing of a man, comes from the Latin root vir, meaning man, from which we also get virile and virtue. The connotation of the word has changed over time: in ancient and early medieval contexts it would have meant a strong female warrior, but by the late middle ages it came to mean a harsh, unattractive and scolding woman.

The novel gives us a little bit of both senses: it’s negative when Marie reflects self-deprecatingly on her own appearance, but a backhanded compliment when the diocesan addresses her as a “noble virago … exalted above all other exemplars of your sex.” It’s part of the deliberate contradiction that the novel explores: Marie’s self-professed “mannish” nature is the very quality that allows her to attain a position of power from which she can uplift other women.

Matrix

“Without the first matrix, there could be no salvatrix, the greatest matrix of all.”

One thing you notice in reading Matrix is all of the words ending in -trix or -rix: cantrix, cellatrix, infirmatrix, hostellerix, scrutatrix, and so on. Each of these words, along with a host of -ess words like almoness and prioress, describes a position in the abbey. Groff never lets the reader forget that each of these roles is performed by women.

The word matrix is itself a -trix word, from the same Latin root that gives us mother. In the novel, it’s used in (at least) two senses: as a personalized seal for inscribing books, and, in the sentence above, as a now-obscure word for womb.

Bonus: alaunt, spavin, mizzling, and a list of 77 other Matrix words here.

Got a book you’d like to see given the “five words from” treatment? Nominate it through this form, or DM us on Twitter!

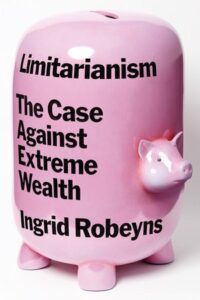

Welcome to the latest installment of “Five words from …” our series which highlights interesting words from interesting books! In this book, Ingrid Robeyns, the Chair in Ethics of Institutions at the Ethics Institute of Utrecht University, outlines the principle she calls limitarianism—the need to limit extreme wealth.

Welcome to the latest installment of “Five words from …” our series which highlights interesting words from interesting books! In this book, Ingrid Robeyns, the Chair in Ethics of Institutions at the Ethics Institute of Utrecht University, outlines the principle she calls limitarianism—the need to limit extreme wealth.