While Shakespeare’s actual date of birth remains unknown, April 23, the date of his death, is celebrated as his birthday. Bardolators pay homage by learning to talk like him and his characters – what better way to start than with insults?

Here we round up ten of our favorite Shakespearean jabs, what they mean exactly, and where they came from.

assinego

Thersites: “Ay, do, do; thou sodden-witted lord! thou hast no more brain than I have in mine elbows; an assinego may tutor thee.”

Act 2. Scene I, Troiles and Cressida

Assinego, also spelled asinego, is “a little ass” or “foolish fellow.” The word comes from the Spanish asnico, diminutive of asno, “ass.”

bed-presser

Prince Henry: “I’ll be no longer guilty of this sin; this sanguine coward, this bed-presser, this horse-back-breaker, this huge hill of flesh,—”

Act 2. Scene IV, Henry IV, Part 1

A bed-presser is someone who’s lazy and loves their bed. Other old-timey synonyms for sluggard include idlesby, loll-poop, curry-favel, and, our favorite, loitersack.

bull’s pizzle

Falstaff: “’Sblood, you starveling, you elf-skin, you dried neat’s tongue, you bull’s pizzle, you stock-fish!”

Act 2. Scene IV, Henry IV, Part 1

This quote from Henry IV is jam-packed with insults. A starveling is someone who is starving but probably means a weakling here. An elf-skin is “a man of shrivelled and shrunken form,” says the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). A neat’s tongue is a tongue of cow or ox, where neat is an obsolete term for a “domestic bovine animal,” and a stock-fish is fish “cured by splitting and drying hard without salt,” perhaps with the idea of something dried up and shriveled.

Finally, a bull’s pizzle is a bull’s penis. The word pizzle comes from a Low German word meaning “tendon,” and is now mostly used in Australia and New Zealand, according to the OED. Penis, in case you were wondering, is Latin in origin.

cullion

Queen: “Away, base cullions!”

Act 1. Scene III, Henry VI, Part 2

A cullion is “a contemptible fellow; a rascal.” An earlier meaning is “testicle,” coming from the Latin culleus, “bag.” See also cully and cojones.

fustilarian

Falstaff: “Away, you scullion! you rampallion! You fustilarian! I’ll tickle your catastrophe.”

Act 2. Scene I, Henry IV, Part 2

Another quote that’s teeming with taunts! A scullion is “a servant who cleans pots and kettles, and does other menial service in the kitchen or scullery,” a rampallion is a villain or rascal, and a fustilarian is a scoundrel.

Fustilarian comes from fustilugs, “an unattractive, grossly overweight person.” Fustilugs comes from a combination of fusty, musty or lacking freshness, and lug, “anything that moves slowly or with difficulty.”

Catastrophe here refers to “the posteriors,” as the OED puts it. So I’ll tickle your catastrophe means something like “I’ll kick your ass.”

harebrained

Charles: “Let’s leave this town; for they are hare-brain’d slaves, / And hunger will enforce them to be more eager.”

Act 1. Scene II, Henry VI, Part 1

Harebrained means having “no more brain than a hare.” Shakespeare’s is the earliest recorded use of this word, which is now often associated with the phrase harebrained scheme.

The earliest mention of harebrained scheme we found was from an 1892 New York Times article: “Of course this is nonsensical, but it appears to have a certain excuse in the fact that the Queen did harbor some such harebrained scheme, and actually summoned Devonshire to Osborne House to discuss it.”

Know of an earlier mention of harebrained scheme? Let us know in the comments.

hobby-horse

Leontes: “My wife’s a hobby-horse, deserves a name / As rank as any flax-wench that puts to/ Before her troth-plight: say’t and justify’t.”

Act 1. Scene II, Winter’s Tale

In this context a hobby-horse is a loose woman or prostitute, according to Gordon H. Williams’s Dictionary of Sexual Language and Imagery in Shakespearean and Stuart Literature. The hobby-horse was “one of the principal performers in a morris-dance,” which says Williams, was “notorious for licentious behaviour under the mask of Maygaming.”

lily-livered

Macbeth: “Go prick thy face, and over-red thy fear, / Thou lily-liver’d boy.”

Act 5. Scene III, Macbeth

Lily-livered means cowardly or timid, and this use in Macbeth seems to be the earliest. Shakespeare seemed to also be the first to use lily to mean pale or bloodless. During Elizabethan times, the liver was believed to be the “seat of love and passion,” according to the Online Etymology Dictionary. As a “healthy liver is typically dark reddish-brown,” a pale liver is presumably unhealthy and weak.

puppy-headed

Trinculo: “I shall laugh myself to death at this puppy-headed monster.”

Act 2. Scene II, The Tempest

Being puppy-headed means being stupid, like a puppy. While puppy at first meant “a small dog kept as a lady’s pet or plaything; a lapdog,” says the OED, by Shakespeare’s time it meant “a young dog.”

In the quote Trinculo is referring to Caliban, “a ‘savage and deformed’ slave of Prospero, represented as the offspring of the devil and the witch Sycorax,” and “figuratively, a person of a low, bestial nature.”

three-suited

Kent: “A knave; a rascal; an eater of broken meats; a base, proud, shallow, beggarly, three-suited, hundred-pound, filthy, worsted-stocking knave.”

Act 2. Scene II, King Lear

Three-suited means having “only three suits of clothes,” and therefore being “beggarly,” or so petty or paltry “as to deserve contempt.” Broken meat refers to “fragments of meat” left after a meal. Worsted stockings seem to be lower quality stockings.

Not insulting enough? Check out these, these, and finally these as told by, what else, cats. Also be sure to see these Wordnik-made lists, Slings and Arrows, 135 Offensive Shakespearean Terms, and today’s list of the day, Knaves, Rogues, and Stewed Prunes. For some now-common words and phrases that the Bard coined or popularized, revisit last year’s post.

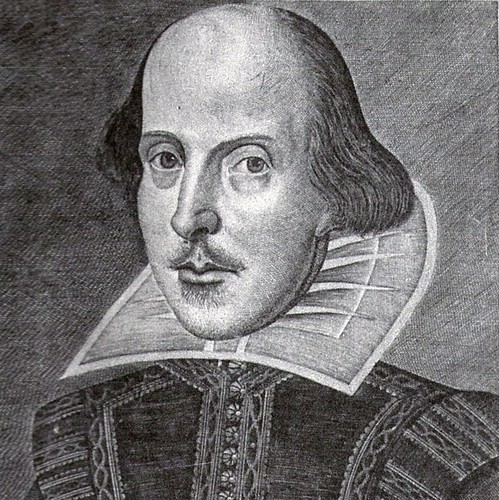

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by tonynetone]