Today’s word of the day is terpsichorean. It means “relating to dancing” or “a dancer.” It comes from the name of Terpsichore, the Greek and Roman Muse of lyrical poetry, choral singing, and dancing.

Today’s word of the day is terpsichorean. It means “relating to dancing” or “a dancer.” It comes from the name of Terpsichore, the Greek and Roman Muse of lyrical poetry, choral singing, and dancing.

Today’s word of the day is sedulous, diligent in application or in the pursuit of an object; constant, steady, and persevering; steadily industrious; assiduous.

Today’s word of the day is mumblement, a low, indistinct utterance or mumbling speech. Of the places we see mumblement being used, we are particularly fond of this little description of the indolent: “idle yawning assistant, with legs stretched out, half asleep, mumblement, jumblement and all” (from The Bertrams by Anthony Trollope). A synonym of mumblement is mussitation, a noun form of mussitate.

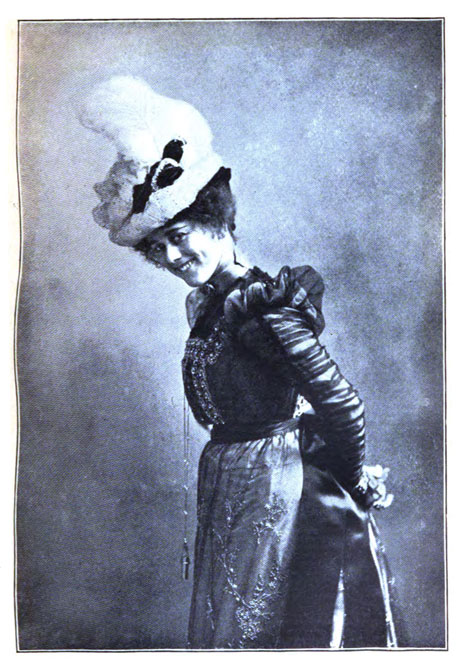

Today’s word of the day is soubrette, a young woman regarded as flirtatious or frivolous. It comes from theatrical comedies and comic opera, in which a soubrette is a saucy, coquettish, intriguing maidservant or the actress taking such a part. The role is usually characterized by pertness and effrontery. Soubrette came into English from French, which took it as soubreto from Provençal, in which it meant “affected” or “conceited.”

Today’s word of the day is cremnophobia, morbid fear of being near the edge of a cliff, precipice, or abyss. Baudelaire, in the poem “Le Gouffre” (“The Abyss”), movingly described that fear (as noted by Max Nordau in Degeneration, 1895).

Here’s a translation of it from the blog “Thrice-Great” which attempted to translate Baudelaire’s poetry collection Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) in a year. Two more translations into English can be found at lesfleursdumal.org. If it’s named fears and not poetry you’re after, try this list of phobias.

Le Gouffre

Pascal avait son gouffre, avec lui se mouvant.

— Hélas! tout est abîme, — action, désir, rêve,

Parole! Et sur mon poil qui tout droit se relève

Mainte fois de la Peur je sens passer le vent.

En haut, en bas, partout, la profondeur, la grève,

Le silence, l’espace affreux et captivant…

Sur le fond de mes nuits Dieu de son doigt savant

Dessine un cauchemar multiforme et sans trêve.

J’ai peur du sommeil comme on a peur d’un grand trou,

Tout plein de vague horreur, menant on ne sait où;

Je ne vois qu’infini par toutes les fenêtres,

Et mon esprit, toujours du vertige hanté,

Jalouse du néant l’insensibilité.

— Ah! ne jamais sortir des Nombres et des Êtres!

Today’s word of the day is seidel, a mug or glass for beer. It comes to English from German, in which language it means stein.

The exact size of a seidel depends upon the place and time. The November 1890 issue of the St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal says it equals a quart. This 1878 table of equivalencies more precisely says that in Austria a seidel was about 0.6229 of a pint, which is about 295 milliliters. Other measures have it from somewhat less than to much more than a quart.

H.L Mencken knew what a seidel was, as well as the full measure of his fellow men: “The average man, at least in England and America, has such rudimentary tastes in victualry that he doesn’t know good food from bad. He will eat anything set before him by a cook that he likes. The true way to fetch him is with drinks. A single bottle of drinkable wine will fill more men with the passion of love than ten sides of beef or a ton of potatoes. Even a Seidel of beer, deftly applied, is enough to mellow the hardest bachelor. If women really knew their business, they would have abandoned cooking centuries ago, and devoted themselves to brewing, distilling, and bartending.” (From Prejucides: Second Series, 1920, New York: Knopf.)

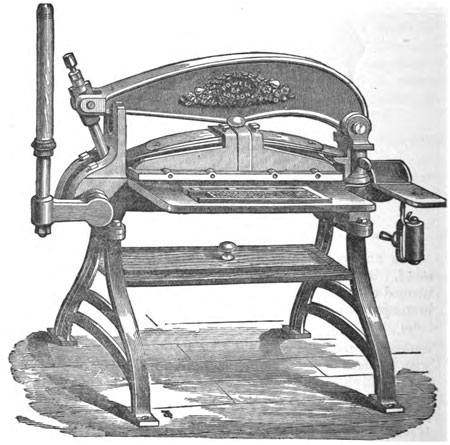

Today’s word of the day is frisket. We chose it because it’s fun to say, even though the meaning is a bit of printer’s jargon. It rhymes with biscuit and brisket. The Century Dictionary defines frisket as “a thin framework of iron hinged to the top of the tympan of a hand-press. For use, a sheet of paper is stretched and pasted over the frisket, and from this paper spaces are cut out to permit contact between the type and the sheet to be printed, which it serves to hold in place when the frisket is folded down upon the tympan, and to keep clean in the parts not printed.” If you want to learn more about old-fashioned printing, we recommend Practical Printing: A Handbook of the Art of Typography by John Southward.