Here at Wordnik we’re all about lists and favorites, so when we review books, we do what we love best: list our favorites.

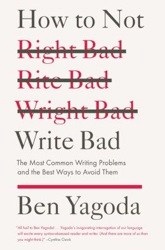

Today we’re looking at a terrific new book from Ben Yagoda, one of our favorite language bloggers: HOW TO NOT WRITE BAD: The Most Common Writing Problems and the Best Ways to Avoid Them. As the title suggests, Yagoda focuses on not how to write well but how to write less badly. After all, “you have to crawl before you walk, and walk before you run.” You have to write “good-enough” before you can even attempt to write like David Foster Wallace.

We liked a lot of things about this book. Here are some of our “five favorites.”

Five favorite terms

bromide

“I imagine the write-what-you-know bromide is mocked because it implies, or seems to imply, that you’re required to write about what you’ve already learned or experienced at the time you sit down at the keyboard.”

A bromide is “a commonplace remark or notion; a platitude,” or “a tiresome person; a bore.” This comes from the chemical sense of the word, “a binary compound of bromine with another element, such as silver,” which was used as a sedative, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary.

Dickens Fallacy

“You could call it the Dickens Fallacy: somehow, we all seem to have an ingrained sense that we’re being paid by the word.”

British writer Charles Dickens was actually paid in installments, not by the word, but the idea of a Dickens Fallacy vividly illustrates some people’s penchant for wordiness. Yagoda’s examples – a verbose sentence followed by his more pared-down version – are helpful in demonstrating not only why concise is better, but how to get there.

frisson

“If I happen to be writing about unfortunate digestive conditions, I can put down diarrea and then diarhea and finally diarrhea – getting a frisson of pleasure from seeing the last one absent of a squiggly red line.”

Frisson is one of our favorite words. It means “a moment of intense excitement; a shudder,” and comes from the Old French fricon, “a trembling.” We also loved Yagoda’s advice about not relying too heavily on spell-check, that it’s “anything but a cure-all and actually can make things worse.” In other words, sometimes spell-check simply won’t help.

gueulade, la

“Gustave Flaubert, renowned as one of the great all-time stylists, used what he called la gueulade: that is, ‘the shouting test.’ He would go out to an avenue of lime trees near his house and, yes, shout what he had written.”

Yagoda suggests reading aloud what you’ve written to catch wordiness, repetition, and “sentences that peter out with a whimper, not a bang.” We’ve tried it, and it works.

skunked words

“The trouble is, like the language itself, the corpus of skunked words is always changing.”

Skunked words are those that were once considered “ignorant, illiterate, unacceptable, etc.,” but have become, by frequent usage, generally accepted. For instance, chomp at the bit was once champ at the bit, stomping ground was stamping ground, and pompom was pompon.

Five questions we had answered by this book

- How do we convince comma-happy people to stop using so many commas?

- What do we tell people who insist that ending a sentence in preposition is wrong (and often go through grammatical gymnastics to avoid it)?

- Why is using “like” okay (sometimes)?

- How do we make a sentence start strong and end strong?

- Why do too many prepositions make a sentence seem weak?

Five words we’d use to describe this book

Useful. How to Not Write Bad is as useful for beginners as for seasoned pros.

Entertaining. One of our favorite lines from the book:

As for sound, students tend to insert commas at places where they would pause in speaking the sentence. This has about the same reliability as the rhythm method for birth control.

Another:

Sitting in class or dancing at a bar, the bra performed well. . .Though slightly pricey, your breasts will thank you.

We’ll never think of dangling modifiers the same way again.

Clear. Yagoda takes his own advice and writes in a clear, concise, and conversational way.

Example-ful. We at Wordnik love examples, and How to Not Write Bad has plenty of them, which do a great job of illuminating Yagoda’s points.

Memorable. Yagoda’s advice for not just correct but strong writing will stay with us for a long time, and we’ll be sure to return to the book for a periodic refresher.