Happy National Punctuation Day!

Where would be without those little dots, dashes, and squiggly lines? You wouldn’t know that we were excited about Punctuation Day, nor would you know that last sentence was a question. But where do these punctuation words come from? We thought we’d take a look at eight of our favorites.

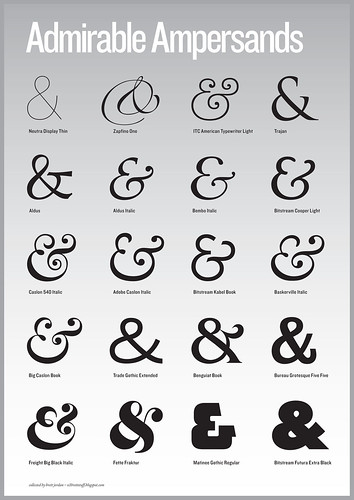

ampersand

“The history of question marks and their ilk turns out to be epic, particularly in the case of the ampersand, whose evolution takes in everything from Julius Caesar to a 17th-century typesetter called Amper (who didn’t actually exist) and even Nazi Germany.”

Johnny Dee, “Internet Picks of the Week,” The Guardian, September 2, 2011

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by Brett Jordan]

The ampersand – or & – represents the word and. The word originated around 1837, says the Online Etymology Dictionary, and is a “contraction of and per se” and means “(the character) ‘&’ by itself is ‘and’.” Furthermore, “in old schoolbooks the ampersand was printed at the end of the alphabet and thus by 1880s had acquired a slang sense of ‘posterior, rear end, hindquarters.’”

Read more about the history of the ampersand.

chevron

“The arches are almost flat, and decorated with a kind of chevron moulding very rarely met with.”

C. King Eley, Bell’s Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of Carlisle

The chevron is also known as the guillemet, “either of the punctuation marks ‘«’ or ‘»’, used in several languages to indicate passages of speech,” and is “similar to typical quotation marks used in the English language.”

While guillemet is a diminutive of Guillaume, the name of its supposed inventor, chevron comes from the Old French chevron, “rafter,” due to the symbol’s similarity in appearance. The Old French chevron ultimately comes from the Latin caper, “goat.” The likely connection, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, is the similarity in appearance between rafters and goats’ “angular hind legs.” Chèvre, a type of goat cheese, is related.

colon

“The colon marks the place of transition in a long sentence consisting of many members and involving a logical turn of the thought.”

Frederick W. Hamilton, Punctuation: A Primer of Information about the Marks of Punctuation and their Use Both Grammatically and Typographically

The colon is “a punctuation mark ( : ) used after a word introducing a quotation, an explanation, an example, or a series and often after the salutation of a business letter.” The word comes from the Latin colon, “part of a poem,” which comes from the Greek kolon, which translates literally as “limb.”

Then there’s the semicolon. Ben Dolnick professed his love for the hybrid punctuation mark, despite Kurt Vonnegut pronouncing semicolons “transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing,” while Stan Carey admitted to being semi-attached to them as well.

comma

“All the interesting punctuation debates I have are internal, as I debate whether or not a comma is necessary in a given spot, or whether two clauses are sufficiently related to be separated by a mere semi-colon.”

“So It’s National Punctuation Day Again,” Motivated Grammar, September 24, 2009

The comma is “a punctuation mark ( , ) used to indicate a separation of ideas or of elements within the structure of a sentence,” and comes from the Greek komma, “piece cut off, short clause,” which comes from koptein, “to cut.”

The comma is a seemingly simple punctuation mark about which people have a lot to say. Earlier this year, Ben Yagoda discussed comma rules and comma mistakes, and addressed some comma questions. At Lingua Franca, he explored some comma beliefs. Stan Carey responded, as did The New Yorker, who defended what Mr. Yagoda called their “nutty” comma style. Johnson questioned the comma splice while Motivated Grammar assured us that comma splices are “historical and informal” but not wrong.

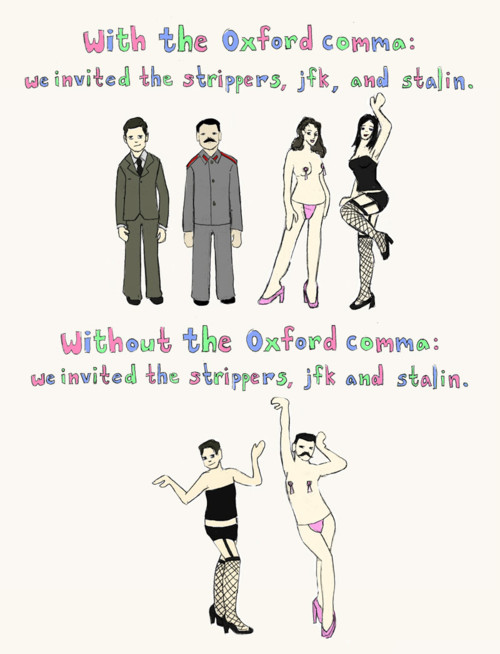

Finally, let’s not forget the importance of the Oxford comma:

For even more about commas, check out our list of the day.

interrobang

“A single character combining a question mark and an exclamation — called an interrobang — didn’t catch on because it doesn’t read well in small sizes and never made it to standard keyboards, while, thanks to email addresses, the @, also known as an amphora, has become ubiquitous.”

Heller McAlpin, “Fond Of Fonts? Check Out ‘Just My Type’,” NPR Books, September 1, 2011

The interrobang, “a punctuation mark in the form of question mark superimposed on an exclamation point, used to end a simultaneous question and exclamation,” comes from a blend of interrogation point, an old term for the question mark, and bang, printers’ slang for the exclamation point.

The at or @ symbol’s “first documented use was in 1536,” according to Smithsonian Magazine, “in a letter by Francesco Lapi, a Florentine merchant, who used @ to denote units of wine called amphorae, which were shipped in large clay jars.”

irony mark

“In 1899, French poet Alcanter de Brahm proposed an ‘irony mark’ (point d’ironie) that would signal that a statement was ironic. The proposed punctuation looked like a question mark facing backward at the end of a sentence. But it didn’t catch on. No one seemed to get the point of it, ironically.”

Mark Jacob and Stephan Benzkofer, “10 Things You Might Not Know About Punctuation,” Chicago Tribune, July 18, 2011

BuzzFeed listed some other punctuation marks you may not have heard of, while The New Yorker tasked readers with inventing a new punctuation mark. The winner was the bwam, the bad-writing apology mark, which “merely requires you to surround a sentence with a pair of tildes when ‘you’re knowingly using awkward wording but don’t have time to self-edit.’” For Punctuation Day, The New Yorker has asked for a punctuation mash-up: “combine two existing pieces of punctuation into a new piece of punctuation.” Check their culture blog for the winners.

punctuation

“The systematization of punctuation is due mainly to the careful and scholarly Aldus Manutius, who had opened a printing office in Venice in 1494. The great printers of the early day were great scholars as well. . . .They naturally took their punctuation from the Greek grammarians, but sometimes with changed meanings.”

Frederick W. Hamilton, Punctuation: A Primer of Information about the Marks of Punctuation and their Use Both Grammatically and Typographically

The word punctuation came about in the 16th century, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and originally meant “the action of marking the text of a psalm, etc., to indicate how it should be chanted.” The word came to mean “system of inserting pauses in written matter” in the 1660s, and ultimately comes from the Latin pungere, “to prick.”

virgule

“Commas were not employed until the 16th century; in early printed books in English one sees a virgule (a slash like this /), which the comma replaced around 1520.”

Henry Hitchings, “Is This the Future of Punctuation?” The Wall Street Journal, October 22, 2011

The virgule, now more commonly known as the slash is “a diagonal mark ( / ) used especially to separate alternatives, as in and/or, to represent the word per, as in miles/hour, and to indicate the ends of verse lines printed continuously.”

Virgule ultimately comes from the Latin virga, “shoot, rod, stick.” Related are verge, virgin, with the idea of a “young shoot,” and virga, an old term for “penis,” as well as “wisps of precipitation streaming from a cloud but evaporating before reaching the ground.”

For even more punctuation goodies, check out Jen Doll’s imagined lives of punctuation marks; McSweeney’s seven bar jokes involving grammar and punctuation; and Ben Zimmer’s piece on how emoticons may be older than we thought. Also be sure to revisit our post from last year on punctuation rules.

Finally, it’s not too late to enter the official National Punctuation Day contest. You have until September 30.

Happy punctuating!