In case you missed it, a contestant on Wheel of Fortune had the most incredible — and luckiest — solve in “30+ years,” says host Pat Sajak. Here’s the video:

Now, what’s incredible isn’t his solving the puzzle with just two letters, but that he came up with, of all things, NEW BABY BUGGY.

New baby buggy? What the heck is that?

This question was posed on my Facebook wall after I posted the video, which made me realize I had no idea. I mean, I know what it is literally — an unused stroller as a (not so) helpful friend pointed out — but what was it? An idiom? A saying? A song lyric?

“It’s a thing,” the same pragmatic friend commented.

Yes, I know, technically it’s a thing, an object, a noun that is neither a place nor a person, but, and John Teti at AV Club would agree, it’s not a thing. It’s a thing but not a thing. Know what I mean?

Search Twitter for the phrase “it’s a thing” and you’ll find a variety of things referenced:

Hugs for hire? Yes, it’s a thing.

We rap country songs now, it’s a thing.

Torture by muffins I don’t have — is this a thing? I think it’s a thing.

These are things that don’t just exist, but as Urban Dictionary says, are phenomena “of some modern cultural significance,” even if ironically. New baby buggies certainly exist. You’ll find them on Diaper.com and Amazon, but are they a cultural phenomena? Unless Wheel of Fortune knows something we don’t know (which I highly doubt), I don’t think so.

While a new baby buggy isn’t a cultural phenomenon, the phrase it’s a thing certainly is. It’s a thing (see what I did there?) — people say it often to describe an unfamiliar occurrence that is familiar to others. For instance:

“I had noodles for my birthday yesterday.”

“Is that a thing?”

“Yes, it’s a Chinese tradition.”

(It was not my birthday yesterday by the way.)

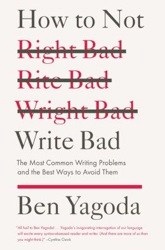

According to this thread on Stack Exchange, the phrase has been in use since as early as the 1990s, specifically on Seinfeld, although no one can find any evidence of this. Linguist Ben Yagoda has an actual citation — a 2001 occurrence on That ‘70s Show:

DONNA: Oh! That’s 16 for me and Hyde and four for the losers! You guys ought to get a mascot … a big, green, furry loser!

ERIC: That’s … That’s not even a thing.

Like new baby buggy, a “big, green furry loser” is not a thing. It’s not a phenomenon nor does it have any cultural significance. It’s random.

So yes, new baby buggy is a thing by grammatical (and Wheel of Fortune) standards, but it’s definitely not a thing. However, one might argue that it’s gaining cultural significance right now, and if it does, my vote would be for it to mean “something presented as though it were thing but is not.” That’s a thing, right?