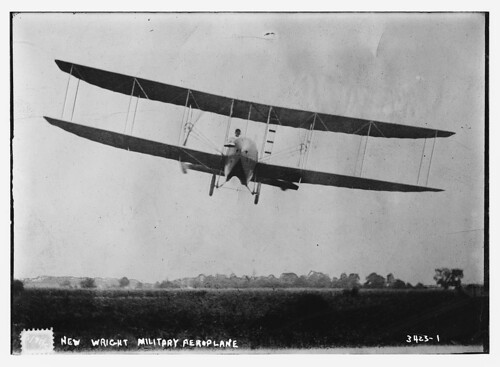

Earlier this week was National Aviation Day, which celebrates the field of aviation and the birthday of airplane innovator Orville Wright. Inspired by this we decided to explore some common words and idioms that you may not know have their roots in flying.

ahead of the curve

“In ‘Insider Baseball,’ her shrewd, funny account of those primaries that is ahead of the curve and galvanized by disgust, Didion would foresee the trivialization and manipulatability of America’s political process to come.”

Sarah Kerr, “The Unclosed Circle,” The New York Review of Books, April 26, 2007

The earliest reported usage of the idiom ahead of the curve, meaning changing before competitors or performing well in general, is from 1926, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The phrase may derive “from the mathematics of flight,” according to World Wide Words, and is also written as ahead of the power curve.

flak

“The Hold Steady always caught flak for being a mock bar band, but somewhere along the way it became an actual bar band.”

August Brown, “Album Reviews,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 2010

Flak, meaning “excessive or abusive criticism or “dissension; opposition,” originally referred to antiaircraft artillery. This latter meaning originated around 1938, coming from the German Flak, which was “condensed from Fliegerabwehrkanone, literally ‘pilot warding-off cannon.’”

The figurative meaning of flak came about around 1968, according to the OED. A flak catcher is “a slick spokesperson who can turn any criticism to the advantage of their employer.” This U.S. colloquialism originated around 1970, says the OED.

gremlin

“While the computer network was fixed by 1.50pm, the gremlin wasn’t found, leaving open the possibility of a repeat performance on any given weekday – when up to 950,000 commuters could be thrown into chaos.”

Joseph Kerr, “CityRail Gremlin Could Strike Any Day,” The Sydney Morning Herald, May 3, 2004

The word gremlin originated as Royal Air Force slang, says the OED, and has been in use since at least 1941. Pilots jokingly attributed inexplicable aircraft mishaps to this mischievous sprite, which later came to embody any type of mischief.

The word may be a combination of the Old English gremman, “to anger, vex,” and the –lin of goblin, or it may come from the Irish gruaimin, “bad-tempered little fellow.”

In the early 1960s, gremlin gained the meaning of “a trouble-maker who frequents the beaches but does not surf,” as per the OED. It was also the (unfortunate) name of a car from the 1970s and a popular movie from the 1980s.

lighter-than-air

“‘Lighter than air,’ said the promotional material for the laptop, which like the Macbook Air has a 13.3-inch screen but which at 1.27 kilograms is 90 grams lighter. That difference is roughly the weight of a cell phone.”

Martyn Williams, “Samsung’s X360: Lighter Than Air — but Not Thinner,” PCWorld, September 5, 2008

The phrase lighter than air, now used figuratively to describe everything from clothes to laptops to frog-leg raviolis, originally referred to lighter-than-air aircraft, which “flies because it weighs less than the air it displaces.” This meaning originated in the 1880s, says the OED.

panic button

“The head coach of the U.S. track and field team said Friday it’s too soon to ‘push the panic button’ over America’s early reversals on the Olympic Games.”

“No Panic Button Yet,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, September 3, 1960

Panic button is slang for “a signal for a hasty emotional response to an emergency.” This figurative sense is from the 1950s and seems to have originated as U.S. Air Force slang, says the OED.

World Wide Words cites a “jokey guide” from 1950 that describes that panic button as “state of emergency when the pilot mentally pushes buttons and switches in all directions.” During the Korean War, pilots who “bailed out at the first sign of action” were disparagingly referred to “as panic-button boys.”

The origin of the panic button may “have been the bell system in the Second World War bombers (B-17, B-24) for emergency procedures such as bailout and ditching, an emergency bell system that was central in the experience of most Air Force pilots.”

push the envelope

“Actor Bob Gerics, who plays Ben in Forest for the Trees, said the company wanted to be able to push the envelope with the show and felt they could do that best in a new venue.”

Kathy Rumleski, “U.S. Playwrights Push the Envelope,” The London Free Press, June 21, 2010

To push the envelope means “to go beyond established limits; to pioneer,” and the envelope here is mathematical, specifically “a curve or surface that is tangent to every one of a family of curves or surfaces.” The flight envelope, as per Cracked, is “the particular combination of speed, height, stress and other aeronautical factors that form the bounds of safe operation.” To go beyond that, or to push that envelope, is both dangerous and, some would argue, pioneering.

According to the OED, the phrase was popularized by Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff.

seat-of-the-pants

“Charismatic, unpretentious, always positive, Couples eschews any kind of deeply thought-out system. Instead he’s a seat-of-the-pants American pragmatist, trying to make things work, lead his team to victory, by muddling through.”

John Paul Newport, “Majesty at Royal Melbourne,” Wall Street Journal, November 19, 2011

Seat-of-the-pants describes something done by intuition or trial and error rather than through careful planning. According to the OED, this phrase originated in the mid-1930s or sooner, referring to “fog-bound pilots without instruments [who] soon learned to tell whether they were flying right-side-up by the pressure against their parachute packs.”

wingman

“Yes, he sounds like a superhero. But ‘Wingman’ is something else entirely. . . . He befriends the BFF, runs interference, breaks the ice, buys drinks. He’s not supposed to win the girl himself.”

John Anderson, “Carrell Has Wingman in ‘Crazy Stupid Love,’” Newsday, July 22, 2011

The modern sense of wingman refers to someone who lends support to a friend trying to attract a love interest. The original meaning, “a pilot whose plane is positioned behind and outside the leader in a formation of flying aircraft,” came about in the early 1940s while the figurative use is from 2006, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary.

However, we found some figurative uses of wingman from before 2006, for instance from August 2004: “Senator John McCain was serving as President Bush’s wingman today as he joined the president for a swing through the Florida Panhandle,” although the only courting here is for votes. This romantic usage is from December 2004: “Those who ride shotgun in the dating world, acting as a wingman or wingwoman, discover there are singles willing to pay for their services.”

If you can find an earlier citation, let us know!

zoom

“Five Russian fighter planes zoomed into Britain’s Berlin-to-Hamburg air corridor Tuesday, the British announced last night.”

“Five Red Fighter Planes Zoom into British Air Lane,” Meriden Record, July 8, 1948

The word zoom meaning “to make a continuous low-pitched buzzing or humming sound” has been around since the late 19th century. However, the word gained popularity around 1917 “as aviators began to use it,” says the Online Etymology Dictionary.

[Photo: No copyright restrictions, The Library of Congress]