Happy Christmas, fellow Wordniks! Today we wrap up our little series on some of our favorite holiday food words. Our final installment, that holiday grog of champions: eggnog.

The origins of both the drink eggnog and the word are unclear. Some say the beverage originated from the 14th century English posset, although posset, while milky, spicy and spiked, doesn’t contain any actual eggs.

As for the word eggnog, the Oxford English Dictionary’s earliest citation is from 1825: “The egg-nog..had gone about rather freely.” However, both Barry Popik and the Online Etymology Dictionary say eggnog is from at least the 1770s. CNN also states the “late 18th century” is the first recorded instance of the term eggnog and even claims that George Washington himself had a recipe.

This genius was hospitalized after “winning” an eggnog chugging contest.

While the egg part of eggnog comes from, well, egg, the nog part is less straightforward. While it originated in the early 1690s and refers to a strong type of beer brewed in Norfolk, England, so say both the OED and the Online Etymology Dictionary, it’s not clear where the word came from. Nug is a possibility, as is noggin, a small cup or mug. By the way, noggin meaning “head” came about in 1769, says the OED, originating from boxing slang.

Finally, think eggnog isn’t anything to get up in arms about? Think again. The Eggnog Riot of 1826, also known as the Grog Mutiny, occurred at the West Point military academy over the course of two days.

What began as a Christmas Day party escalated into destructive drunkenness as cadets downed whiskey-laden eggnog, broken windows, and fired weapons willy-nilly, (which just goes to show white people have been rioting over dumb stuff for a long time). One of the rioters was none other than Jefferson Davis, future president of the Confederate States of America.

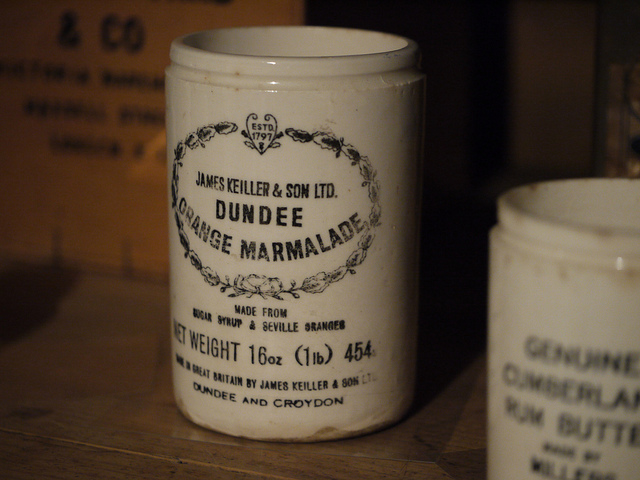

In case you missed it, check out our posts on clementines, Dundee cake, and panettone.

[Photo via Flickr, “Eggnog,” CC BY 2.0 by Natalie Maynor]