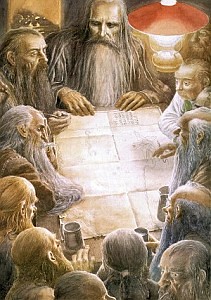

We here are Wordnik are quite excited that The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey opens today. While we didn’t go as far as to don Hobbit ears and wizard caps and camp out in front of our favorite theater, we did gather 10 of our favorite journey words (not Journey words) right here.

booze cruise

“The head of the Massachusetts Port Authority resigned yesterday after it was learned that he went on a ‘booze cruise‘ paid for by his agency during which a woman bared her breasts.”

“‘Booze Cruise’ Flap Ousts Board Head,” Toledo Blade, August 19, 1999

In American English, booze cruise refers to “a recreational trip on a cruise ship or boat usually tailored to young people, with the expectation of heavy consumption of alcoholic beverages.” This meaning originated around 1979, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

The British English meaning, “a brief trip from Britain to France and/or Belgium in order to buy alcohol (or tobacco) in bulk quantities without paying excise duty,” is newer, coming about in the mid-1990s, says the OED.

The word booze comes from the Middle English bousen, “to drink to excess.”

jaunt

“Such a jaunt was a rare treat to the child, for Isabella Spencer seldom allowed her to go from home with anybody but herself.”

L.M. Montgomery, Further Chronicles of Avonlea

A jaunt is “a ramble; an excursion; a short journey, especially one made for pleasure.” An earlier definition was “tiresome journey,” says the Online Etymology Dictionary, and earlier than that was the verb sense, “tire a horse by riding back and forth on it.” The origin is unknown, perhaps coming from “some obscure Old French word.”

Jaunty, “having a buoyant or self-confident air” or “crisp and dapper in appearance,” has a different origin, coming from the French gentil, “nice,” which in Old French means “noble.”

junket

“Businesses are providing lavish junkets to little-known but highly-influential staff across swathes of the public sector, a Sunday Herald investigation can reveal.”

Paul Hutcheon and Tom Gordon, “Junket Scotland,” Herald Scotland, October 18, 2008

A junket is “a trip or tour,” especially “one taken by an official at public expense.” The word’s earliest meaning is “a basket made of rushes,” or a type of marsh plant; then, “curds mixed with cream, sweetened, and flavored,” and by extension, “any sweetmeat or delicacy.”

The meaning shifted in the 1520s, says the Online Etymology Dictionary, to “a feast or merrymaking; a convivial entertainment; a picnic.” The led to the sense of “pleasure trip,” and to the American English meaning, around 1886, of “tour by government official at public expense for no discernable public benefit.”

The word ultimately comes from the Latin iuncus, referring to the rush marsh plant. Iuncus also gives us junk, originally a nautical term meaning “old or condemned cable and cordage cut into small pieces,” perhaps named for its similarity in appearance to the reedy marsh plant.

milk run

“Tired of the same old ‘milk run‘ to work every morning? Try the ‘computer run.’”

“Coming Next, The Morning Computer Run,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, July 23 1966

A milk run is “a routine trip involving stops at many places,” as well as “an uneventful mission, especially a military sortie completed without incident.”

The phrase, which originated around 1909, seems to come from older milk round (1865), which, according to the OED, is “a fixed route on which milk is regularly collected from farmers or delivered to customers; a milk delivery business covering such routes.” Milk round gained the figurative meaning of “a series of (typically annual) visits to universities and colleges made by business representatives to recruit graduates.”

mush

“I just came in from a seventy-five mile ‘mush,’ but will start to-morrow for Chena. Nearly all our people are going or have gone. I have no dogs, but combine with two other fellows and pull our sleds.”

“The Assembly Herald,” Presbyterian Magazine

Mush, which is “used to command a team of dogs to begin pulling or move faster,” also refers to the journey itself, “especially by dogsled.” Earlier was the verb sense, “to trudge or travel through the snow, while driving a dog-sled.” The word may come from the French marcher, “to walk, go.”

peregrination

“After slipping among oozy piles and planks, stumbling up wet steps and encountering many salt difficulties, the passengers entered on their comfortless peregrination along the pier; where all the French vagabonds and English outlaws in the town (half the population) attended to prevent their recovery from bewilderment.”

Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit

A peregrination is “a traveling from one country or place to another; a roaming or wandering about in general; travel; pilgrimage.” The word ultimately comes from the Latin peregrinus, “from foreign parts, foreigner.” The first child born in Plymouth Colony was Peregrine White, where peregrine means “a foreign sojourner.”

sally

“Even a captain in war must know the special virtues and vices of the enemy: which nation is ablest to make a sudden sally, which is stouter to entertain the shock in open field, which is subtlest of the contriving of an ambush.”

Clare Howard, English Travellers of the Renaissance

A sally is “a run or excursion; a trip or jaunt; a going out in general,” and comes from the Latin salīre, “to leap.”

Sally, the proper name, is an alteration of Sarah. Sally Ann is a nickname for the Salvation Army.

sashay

“I fell down eleven steps into your garden, knocked on the front door, knocked on the side door, talked to some one called ‘Ma,’ talked to some one called ‘Lydia,’ and learned that Miss Martha Brunhilde Monroe was out for a sashay.”

Kathleen Thompson Norris, Martie, The Unconquered

Sashay, which has the more common meaning of “to walk or proceed, especially in an easy or casual manner,” or “to strut or flounce in a showy manner,” also refers to “an excursion; an outing.” The word is what the Online Etymology Dictionary calls a “mangled Anglicization” (manglicization?) of the French chassé, “gliding step.”

schlep

“This election season, Jewish grandchildren all over the United States are schlepping to crucial swing states such as Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Michigan to convince their grandparents to vote for Obama as part of The Great Schlep, a project of the Jewish Council for Education and Research.”

Nandini Balial, “Students ‘schlep’ To Sway Relatives To Obama,” CBS News, February 11, 2009

A schlep is “an arduous journey,” and is Yiddish in origin, coming from shlepn, “to drag, pull.” This sense of schlep entered English in the 1960s, says the OED.

walkabout

“When the royal couple arrived for a ‘walkabout‘ in some town and split up the street — Charles heading to one side, Diana to the other — people on Charles’ side of the street would groan audibly: they had wanted HER and got stuck with HIM.”

Pat Morrison, “Sarah Palin and Princess Diana,” The Huffington Post, September 12, 2008

Walkabout has multiple meanings associated with a journey: in Australia, “a temporary return to traditional Aboriginal life, taken especially between periods of work or residence in white society and usually involving a period of travel through the bush”; “a walking trip”; and, chiefly British, “a public stroll taken by an important person, such as a monarch, among a group of people for greeting and conversation.”

This last sense is the newest, originating around 1970, according to the OED, while the other senses are attested to the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

[Photo: CC BY-SA 2.0 by loresui]