Welcome to this week’s Language Blog Roundup, in which we bring you the highlights from our favorite language blogs and the latest in word news and culture.

We were saddened by the passing of Aaron Swartz, “computer programmer, writer, political organizer and Internet activist.” Ben Zimmer wrote about Infogami, a startup Swartz founded, while Geoffrey Pullum discussed “vague and lazy talk” about hacking.

For Inauguration Day, the Smithsonian offered visualizations of the meaningful words behind famous inaugural speeches; Ben Zimmer discussed words coined by U.S. presidents; and The New Yorker gave us a brief history of inaugural poems.

The New York Times reported that in the debate on gun control, even the language can be loaded, while at Johnson, Robert Lane Greene wondered if changing one word could change American opinions.

Johnson also discussed the language of gender and sexual orientation, a short history of you, and the singular they, about which folks had a lot to say, including Jen Doll (against), John McIntyre (for), and the Oxford Dictionaries blog (neutral).

At Lingua Franca, William Germano examined Treasury Secretary Jack Lew’s signature and the paraph, “that flourish-y bit below a signature,” as well as catfishing and imaginary online friends. Geoff Pullum considered being an adjective, Lucy Ferriss peeked under the lid, and Ben Yagoda went po-faced.

At Macmillan Dictionary blog, Stan Carey mansplained the new-word-pocalypse, and on his own blog, played usage peeve bingo. In the week in words, Erin McKean noted jukochodai, old-school manufacturers; slow steaming, a technique for slowing down ships; laolaiqiao, “old people doing young things that even young people wouldn’t do.”

Fritinancy looked at drusy, “a crust of small crystals lining the sides of a cavity (or vug) in a rock”; snollygoster, “a shrewd, unprincipled person, especially a politician”; and some moist slacks (ew). She also discussed how to name anything.

Sesquiotica gave us a taste of phonemes, long and short vowel pairs, finicky, and frisky. The Dialect Blog dialogued on the Jamaican rounded schwa, and the Virtual Linguist told us about Silbo Gomero, “an old whistling language used on the Canary island of Gomera.”

Ben Yagoda discussed the Britishism have (someone) on. Allan Metcalf told us about a new crowdsourced Jewish English lexicon, Slate’s Lexicon Alley explained the origins behind the New York accent, and Chicago Magazine mapped the geography of Chicago’s second languages.

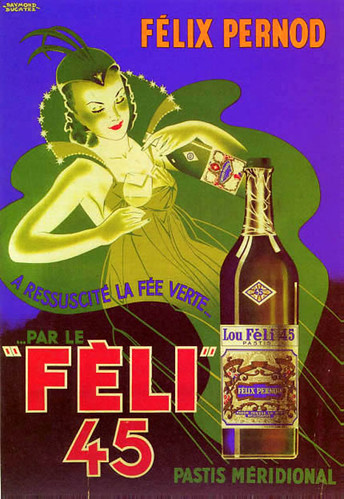

IBM’s supercomputer, Watson, is learning some slang; OxfordWords blog taught us slang of the prohibition era; and Jonathan Green gave us 50 (we think!) slang words that come from snow. The Economist discussed how the press in China is getting around censorship, while O Canada told us about a campaign to save old words, with quotes from Jesse Sheidlower, Mark Liberman, and our own Erin McKean.

This week we also learned a brief history of the dictionary, that Emily Dickinson scrawled her poems on tiny scraps of paper, how to insult in Lutheran, and how to speak Ned Flanders. We found out why the blues is called the blues, the science behind beatboxing, and why people roll their eyes when they’re annoyed.

We’re glad to see Ben Schmidt is still collecting anachronisms from Downton Abbey. We agree that editors are important and that cheesemongers do indeed pen some clever descriptions. We loved these best shots fired in the Oxford comma wars, these 16 great library scenes, and this amazing library (although the idea of robot librarians scares us a little). And then our heads exploded imagining all 11 Doctor Whos in one anniversary special.

We’d like to order all of these coffee drinks, then stay up all night playing these literary board games. We chuckled over these light bulb jokes for the publishing industry and are currently memorizing these 17 vowel free words that are acceptable in Words with Friends. We liked these lolcats of the Middle Ages and awww’d over this catalog of bookstore cats.

That’s it for this week! Until next time, have a dandy-diddly day-di-iddlyo!

[Photo: CC BY 2.0 by Sarah Stierch]

![[ T ] John Tenniel - Alice Through the Looking-Glass (1871)](http://farm6.staticflickr.com/5212/5485576189_14061e9d8b.jpg)